After many years of waiting, Roger’s opera Ca Ira saw it’s premièr performance in Rome on 17 November 2005.On this page, you can read reviews of the opera (Both the live performance, and the DVD) see a bunch of pictures, and read up on the background.

The Times November 19, 2005

Pink Floyd never sounded like this (nor did Puccini) From Richard Owen in Rome

ROGER WATERS awoke yesterday to reviews judging him not as the famous co-founder of Pink Floyd but as an aspiring composer of opera.

ROGER WATERS awoke yesterday to reviews judging him not as the famous co-founder of Pink Floyd but as an aspiring composer of opera.

Back in the summer the long-estranged Waters and Dave Gilmour played together for the first time in a quarter of a century, at the Live 8 concert in Hyde Park. This week Pink Floyd were inducted into the Hall of Fame at Alexandra Palace, with Waters taking part by satellite link from Rome.

His new incarnation is as composer of Ça Ira, a three-act opera about the French Revolution that took 16 years to write. The aim, he said, after the world premiere in Rome, remained to “create an emotional response”, and his inspiration came from Mahler, Brahms, Prokofiev, Verdi, Donizetti and Puccini. As Waters, 61, bounded on stage to greet the sell- out audience in Italian at Rome’s Music Auditorium, however — all open-necked shirt, craggy features and flowing silver hair — the standing ovation was as much for the rock legend as for Ça Ira.

“Waters is not so much Verdi or Puccini, more Andrew Lloyd Webber,” La Repubblica said. The opera was “eclectic” and derivative, with more “songs” than arias, and relentless crescendos in the style of Carl Orff. It was “like an elephant trying to take to the air with a small pair of wings”.

Yet what a bravura performance, said Il Messaggero, the Rome daily. It praised the staging and sound-effects, from cannon fire and the swish of the guillotine, to birdsong at Versailles and the ominous cawing of crows as Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette approach their doom. A chorus of young voices — reminiscent of Pink Floyd’s The Wall — provides a poignant counterpoint.

Yet what a bravura performance, said Il Messaggero, the Rome daily. It praised the staging and sound-effects, from cannon fire and the swish of the guillotine, to birdsong at Versailles and the ominous cawing of crows as Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette approach their doom. A chorus of young voices — reminiscent of Pink Floyd’s The Wall — provides a poignant counterpoint.

Waters was philosophical: the knives had been bound to come out, and at least his work was “genuine”. He had been working on the opera since the bicentenary of the revolution, when his friends Etienne and Nadine Roda-Gil asked him to set their libretto to music. The theme, he said, was not unlike The Wall: despair and deprivation giving birth to hope and the human spirit.

Ça Ira (literally “It Will Go” but meaning something more like “There is Hope”) is clearly inspired as much by the Paris of 1968 as by the Paris of 1789. Waters met Etienne Roda-Gil — who wrote songs for Juliette Greco, among others — during the 1968 student revolt.

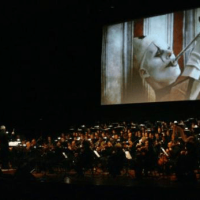

Ça Ira was performed by the Rome Sinfonietta, under Rick Wentworth, the cast including the British singers Sarah Leonard and Keel Watson.

As for Pink Floyd, a further reunion was very unlikely, even though he had enjoyed the Live 8 reunion, he said. At Alexandra Palace, Gilmour had been in similar mood: “The Live 8 moment was a wonderful moment, but we’ve moved on and there are lots of other things to be thrilled about these days.”

Sueddeutsche Zeitung. 19 Nov. 2005

Roger welcomed the audience in Italian, knowing that English is not “the fine way” here in Rome.

any years to write this opera, or at least what he thinks is an opera. It was obvious that this couldn’t have been easy for him, compared to his music in the past.

It was hard to understand how it had taken him 15 years of work, but the fact is that this is his first attempt to classical music.

The word opera in this case is misunderstood. Etienne Roda-Gil wrote a narration for a single person to read. The appearance of libretto-events with no pause or stop, no middle, and no great finale, has forced Waters to take shortcuts.

The yearning of many pop musicians to write for a classical orchestra easily understood, but in practice leads to nothing, because pop music does not need the complexities and difficult apparatus of classical music.

The yearning of many pop musicians to write for a classical orchestra easily understood, but in practice leads to nothing, because pop music does not need the complexities and difficult apparatus of classical music.

Roger Waters obvious talent for composing complex shapes and soundbuilding is missing here. Rick Wentworth has tried to rectify this, but where there is nothing to find, there is nothing you can do.

The classical elements such as duos, triois or quartetts are missing completely. And such pieces must be in an opera to give the piece a kind of structure.

But being the first classical piece written by him, its not so bad. He needs some more efforts to come along with the difficulties and details of classical music”

Thanks to Torsten for the translation.

By AFG staffer Robyn Moran

(Images from the DVD)

It’s stating the obvious when I say opera is not for everyone. When you’ve grown up on a diet of rock music like I have, opera is totally alien to the uninitiated.

It’s stating the obvious when I say opera is not for everyone. When you’ve grown up on a diet of rock music like I have, opera is totally alien to the uninitiated.

On the other hand, if you enjoy a good story and great music and if you are able to understand most of the words to the songs, you’ll be swept along on a journey that can only be better if you could watch the events unfold on stage.

Listening to an opera before you see it is like listening to a play before you see it. Nevertheless I found by listening to the sound track first, it brings the music to the fore without visuals getting in the way.

An opera based on the French Revolution requires a mighty powerful score and I believe (in my humble and inexperienced opinion) Roger has delivered.

An opera based on the French Revolution requires a mighty powerful score and I believe (in my humble and inexperienced opinion) Roger has delivered.

When you hear the first bars of the overture, the distant sound of a dog barking and of calling birds, the Pink Floyd influence is immediately evident and promises an exciting ride.

The overture entitled The Gathering Storm is spine chilling one minute and wildly exciting the next when the music changes unmistakably to the electric atmosphere of the circus ring where the opera takes place; audience and performers changing places throughout the show.

The story is told through music and song using adult and children’s voices, marching feet and drums, explosive canon and gunfire, even a scratching quill.

The story is told through music and song using adult and children’s voices, marching feet and drums, explosive canon and gunfire, even a scratching quill.

There are sequences with African music, the fall of the Bastille and an ecclesiastic sequence which all help tell the story of the people’s plight and their desperate struggle for liberty, fairness and justice.

Finally the execution of Louis and Marie Antoinette are carried out and the age old questions are raised again which are still asked today. Is there justification to use violence to achieve peace?

Some words are lost in the very high and very low ranges or when a mob of people are singing but overall the story is easy to follow, forever moving and changing direction and I’d love to watch the opera to tie it all together.

Harry & India Waters can be seen standing just left of centre.

Thanks to Nicola

An Opera in Three Acts

by Roger Waters

From the original libretto by Etienne & Nadine Roda-Gil

It is perhaps surprising, given the cataclysmic nature of an event which the historian A.J.P. Taylor referred to as “the end of a world”, that the French Revolution has served so rarely, except as deep and obscure background, as a source of inspiration to the great librettists and composers of C19th and C20th Opera. With some little prompting most opera lovers would no doubt be able to cite Giordano’s Andrea Chenier as a notable exception to this lapse, but it would surely require an especially devoted aficionado to call up von Einem’s Danton’s Death and Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites without considerable and prolonged delving. None of these works is universally celebrated by frequent performance, nor do any of them maintain places in one’s general awareness of the world of music which correspond to those held, for example, by Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution, and Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel in one’s general awareness of the world of literature. Perhaps the terror of 1793, with its spies and informants, its executions and imprisonments, subsequently offered so many dramatic possibilities to the creative imagination, particularly in the deaths of rich and aristocratic, and therefore famous people, that it smothered any impulse to depict the ideals and aspirations which initiated the revolution, all too quickly became its only story, and grew overly familiar and exhausted of genuine interest in the process. Whatever the case, one is left wondering at the fact that the epic events of the early revolutionary years, of which the fall of the Bastille and the march of 7,000 bedraggled women on Versailles are merely the best known, as well as the spirit of hope and the w ill for beneficial change which informed t hem, have so seldom and so perfunctorily engaged the foremost talents of an art form which through its combination of voice, orchestra, and theatre is arguably the one best equipped to present them.

It is perhaps surprising, given the cataclysmic nature of an event which the historian A.J.P. Taylor referred to as “the end of a world”, that the French Revolution has served so rarely, except as deep and obscure background, as a source of inspiration to the great librettists and composers of C19th and C20th Opera. With some little prompting most opera lovers would no doubt be able to cite Giordano’s Andrea Chenier as a notable exception to this lapse, but it would surely require an especially devoted aficionado to call up von Einem’s Danton’s Death and Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites without considerable and prolonged delving. None of these works is universally celebrated by frequent performance, nor do any of them maintain places in one’s general awareness of the world of music which correspond to those held, for example, by Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution, and Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel in one’s general awareness of the world of literature. Perhaps the terror of 1793, with its spies and informants, its executions and imprisonments, subsequently offered so many dramatic possibilities to the creative imagination, particularly in the deaths of rich and aristocratic, and therefore famous people, that it smothered any impulse to depict the ideals and aspirations which initiated the revolution, all too quickly became its only story, and grew overly familiar and exhausted of genuine interest in the process. Whatever the case, one is left wondering at the fact that the epic events of the early revolutionary years, of which the fall of the Bastille and the march of 7,000 bedraggled women on Versailles are merely the best known, as well as the spirit of hope and the w ill for beneficial change which informed t hem, have so seldom and so perfunctorily engaged the foremost talents of an art form which through its combination of voice, orchestra, and theatre is arguably the one best equipped to present them.

Of course, as we were buffeted towards the close of the last and most turbulent of centuries, our course marked out by relentless catastrophe on a scale previously unimaginable, and beset by political, social, and scientific ‘revolutions’ so frequent that our capacity for shock, incredulity, and awe was almost entirely dulled, it required some substantial and public reminder of the French Revolution to suggest its distant gestures of dissent as a subject worthy of art, and to concentrate our minds once again on their connection and continuing relevance to us. The celebrations commemorating the Revolution’s Bicentennial in Paris throughout 1989 neatly fitted that bill, and in one instance at least acted as a potent and fruitful catalyst for an intense creative effort. The project upon which the respected and successful songwriter Etienne Roda-Gil was working, and which w as intended to have been included amongst t he commemorative events, turned out to be a full operatic libretto. Entitled Ca Ira, after the revolutionary song, the manuscript, copiously and beautifully illustrated by Roda-Gil’s wife, Nadine, attempted to portray the events and spirit of the revolution’s early stage and brief period of accomplishment as they were perhaps witnessed and felt by the many and various participants whose voices struggled to be heard above the tumult of that prolonged and shattering upheaval.

Of course, as we were buffeted towards the close of the last and most turbulent of centuries, our course marked out by relentless catastrophe on a scale previously unimaginable, and beset by political, social, and scientific ‘revolutions’ so frequent that our capacity for shock, incredulity, and awe was almost entirely dulled, it required some substantial and public reminder of the French Revolution to suggest its distant gestures of dissent as a subject worthy of art, and to concentrate our minds once again on their connection and continuing relevance to us. The celebrations commemorating the Revolution’s Bicentennial in Paris throughout 1989 neatly fitted that bill, and in one instance at least acted as a potent and fruitful catalyst for an intense creative effort. The project upon which the respected and successful songwriter Etienne Roda-Gil was working, and which w as intended to have been included amongst t he commemorative events, turned out to be a full operatic libretto. Entitled Ca Ira, after the revolutionary song, the manuscript, copiously and beautifully illustrated by Roda-Gil’s wife, Nadine, attempted to portray the events and spirit of the revolution’s early stage and brief period of accomplishment as they were perhaps witnessed and felt by the many and various participants whose voices struggled to be heard above the tumult of that prolonged and shattering upheaval.

Such topics and themes inevitably attracted Roda-Gil anyway. Bom to a working class Catalan family that escaped Franco’s tyranny in Spain by fleeing to France, Roda-Gil inherited his father’s communist ideals as well as his rebellious instincts. Powerful elements of both naturally feature in his work, hi fact, his first major success as a ‘parolier’ was with La Cavallerie, a lyric he wrote for the young Julien Clerc which employed one of the catchphrases of the 1968 student uprising. “Et j’abolirai 1’ennui” (And I’ll abolish boredom) was also a rallying cry for the (French) Situationists in whose intellectual and political circles Roda-Gil then moved. The song was a big hit, and began a long though not exclusive collaboration between Roda-Gil and Clerc. Other artists with whom he enjoyed successful partnerships include names as diverse as Juliette Greco and Johnny Hallyday. The most recent of these, however, and the one which continued until his death in May 2004 was with Roger Waters who wrote the rail orchestral score for £a Ira, as well as an entirely new set of English lyrics.

Such topics and themes inevitably attracted Roda-Gil anyway. Bom to a working class Catalan family that escaped Franco’s tyranny in Spain by fleeing to France, Roda-Gil inherited his father’s communist ideals as well as his rebellious instincts. Powerful elements of both naturally feature in his work, hi fact, his first major success as a ‘parolier’ was with La Cavallerie, a lyric he wrote for the young Julien Clerc which employed one of the catchphrases of the 1968 student uprising. “Et j’abolirai 1’ennui” (And I’ll abolish boredom) was also a rallying cry for the (French) Situationists in whose intellectual and political circles Roda-Gil then moved. The song was a big hit, and began a long though not exclusive collaboration between Roda-Gil and Clerc. Other artists with whom he enjoyed successful partnerships include names as diverse as Juliette Greco and Johnny Hallyday. The most recent of these, however, and the one which continued until his death in May 2004 was with Roger Waters who wrote the rail orchestral score for £a Ira, as well as an entirely new set of English lyrics.

Introduced to the songwriter by a mutual friend, Waters was instantly impressed by Roda-Gil’s manuscript. Especially drawn to the subject matter and taken by Nadine’s illustrations that provoked a few early ideas for future staging, Waters enthusiastically embraced the challenge of writing the musical score. This interest and determination were not, perhaps, as surprising as one might at first have thought them to be. Waters’ internationally acclaimed work with Pink Floyd, one of whose founder members he was, and whose major creative force he’d been for more than two decades prior to embarking on a successful solo career, has a good deal of the epic about it, and in pieces such as Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, and The Wall engages similar themes of individual struggle, change, and the need for honesty, truth, and fairness in both our social and political arrangements. Always concerned to increase the impact of his art on his vast audience, as well as to enhance its capacity to entertain, his performances incorporated liberal and imaginative use of theatre. The Wall, for example, brought together narrative^ drama, music and song – precisely those elements which opera buffs would recognise as their own — in a full scale and spectacular ‘coup de theatre’.

Introduced to the songwriter by a mutual friend, Waters was instantly impressed by Roda-Gil’s manuscript. Especially drawn to the subject matter and taken by Nadine’s illustrations that provoked a few early ideas for future staging, Waters enthusiastically embraced the challenge of writing the musical score. This interest and determination were not, perhaps, as surprising as one might at first have thought them to be. Waters’ internationally acclaimed work with Pink Floyd, one of whose founder members he was, and whose major creative force he’d been for more than two decades prior to embarking on a successful solo career, has a good deal of the epic about it, and in pieces such as Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, and The Wall engages similar themes of individual struggle, change, and the need for honesty, truth, and fairness in both our social and political arrangements. Always concerned to increase the impact of his art on his vast audience, as well as to enhance its capacity to entertain, his performances incorporated liberal and imaginative use of theatre. The Wall, for example, brought together narrative^ drama, music and song – precisely those elements which opera buffs would recognise as their own — in a full scale and spectacular ‘coup de theatre’.

Working alone in his own studio, and using a string synthesiser to simulate percussion, strings, and brass, Waters quickly produced a rough demo of music in the C19th orchestral tradition on which he also sang the various vocal leads. The tape soon came to the attention of the authorities at the Opera Bastille, the new opera house in Paris, and for some weeks there was talk that £a Ira might very well provide one of its inaugural shows. Despite a personal recommendation from the then French President, Franfois Mitterrand, who had privately heard the demo and publicly expressed his admiration for it, this didn’t happen: personnel changes high up in the Opera Bastille’s administration scuppered a good deal of its early programming. Soon afterwards the illness and subsequent death of Roda-Gil’s wife, Nadine, put the project on hold for several years.

A substantial loose end amongst his creative projects, and one whose further development represented an enormous challenge in terms of (for him) new compositional techniques, Waters was bound to return to it. Re-establishing contact with Roda-Gil in the early ’90s, as well as enlisting the help of film score composer and Royal Academy of Music faculty member, Rick Wentworth, he set about refining and extending the early “draft” score of his demo into an authentically monumental and polished work for full orchestra and voices.

At its most optimistic and triumphant, the French Revolution appeared to herald a new age which was to be characterised by a new morality and a new ethical system based on justice, kindness and generosity. In £a Ira Waters and Roda-Gil concentrate on this spirit and use the revolution as a metaphor for the strength and p6wer of human change and growth. As the last line of the English libretto has it: “The promise of the Republic lies within”. With thrilling operatic grandeur Ca Ira reminds us all of that promise, and of that hope.

Ca Ira debuts at Number One on Billboard Charts. After it’s release on 27 Sept, Roger Waters opera has rocketed to the top of the Billboard Traditional Classical Chart. Ca Ira gets it’s debut in Rome on November 17th & 18th.

***

Ça Ira now on sale. You can access more details on Roger’s official site In addition, you may chose to pre-order from Amazon where you will be assisting in the maintenance of this site. Hybrid SACD/DVD DigiPack with 60 page book | Standard audio CD

***

Ça Ira to Premier in Rome The world premier of Roger Waters long awaited opera Ça Ira will take place at the Auditorium Parco Della Musica in Rome on 17 November. The 100 strong Rome Sinfonietta will be used in the production, along with a chorus of 80, which includes many children. Due to strong ticket sales for the performance on the 17th, an additional date of the 18th has now been announced.

Critic’s Notebook – September 28, 2005 When Rockers Show Classical Chops By ALLAN KOZINN – NYTimes

With “Ça Ira,” his new opera about the French Revolution, just released on a Sony Classical recording, Roger Waters joins a parade of rock stars who apparently harbor dreams of tuxedos and podiums. Sir Paul McCartney has written a handful of orchestral and choral works, large and small. Stewart Copeland, of the Police, beat Mr. Waters to the punch with his own opera, “Holy Blood and Crescent Moon.” Billy Joel has recorded an album’s worth of piano pieces, and Elvis Costello, with a ballet behind him, has written an opera as well.

It seems to be a part of the human condition that having established a specialty, we hanker to do something else. And far be it from me to say that we shouldn’t. But speaking as a classical music critic who also listens to lots of rock – and who wishes that more rock fans found classical music exciting as well – I must confess that I find many of these crossover incursions dispiriting.

For one thing, rock stars who become interested in classical music are bizarrely conservative. They may play the most electrifying, guitar-thrashing, edge-of-the-seat stuff with their own bands, but when they decide to write classical music, or what they think of as classical music, they reach for a quill instead of a pen. With the notable exception of Frank Zappa, whose reams of classical music reflect his fascination with Edgard Varèse and other modernists, rock musicians seem to think that the conventions of the 19th century are classical music’s current language. Mr. Waters ought to have escaped that conservatism. His former band, Pink Floyd, was known for its almost symphonic experiments in timbre, structure and controlled dissonance. Its quasi-operatic magnum opus, “The Wall,” was thoroughly Mr. Waters’s baby.

Yet the overture to “Ça Ira” (“So It Will Be”) is couched in Brahmsian moves and sonorities, and the work rarely lurches forward. A listener soon bumps into orchestral effects that have their roots in Beethoven’s “Egmont” or, in more adventurous passages, Puccini’s “Tosca” or the Battle on the Ice from Prokofiev’s “Alexander Nevsky.” Maybe Mr. Waters is mistaken to call this an opera. Yes, there are operatic things about it. The vocal writing is lyrical and often attractive, even if there is little in the way of full-fledged aria writing. There is a hefty amount of choral music, and it is supported by a rich orchestral score. (Mr. Waters had some help in the orchestration from Rick Wentworth, who conducts the recording.) And there are recognizably operatic voices: the baritone Bryn Terfel, the tenor Paul Groves and the soprano Ying Huang each sing several roles.

But if you were to walk into a room in which the CD happened to be playing, you would be far less likely to say, “Hey, it’s an opera” than “Hey, it’s one of those overblown musicals that have taken over Broadway” – or words to that effect. If you were feeling charitable, you might add, “At least it’s a few steps closer to Stephen Sondheim than to Andrew Lloyd Webber” – although if you stay long enough, you’ll go back and forth on that one, possibly settling on Claude-Michel Schönberg’s score for “Les Misérables.”

From a purely theatrical point of view, “Ça Ira” has a few nice touches: not least, the idea of presenting the early stages of the French Revolution as a three-ring circus, with the Ringmaster (one of Mr. Terfel’s roles) as a kind of singing history book and commentator. And it deals artfully with serious issues like tyranny, power, liberty and the difficulty of preventing revolutionary passions from being transformed into a form of terror that threatens to negate what has been gained.

No doubt there are some in classical music circles who see a sterling opportunity here, and a decade ago, I would have been one of them. In theory, rock stars who write classical works are telling their audiences that they see something special in this music, something inspiring in the old forms and in the idea of writing for orchestra and unamplified voices. And it isn’t unreasonable to expect that a new audience might be enlisted from fans who want to understand what drives their heroes, and who want to like what their heroes like.

When rock fans in the United States bought the first albums by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Kinks, they encountered cover versions of American rhythm-and-blues hits that white American listeners had ignored, and they quickly sought out the originals. Linda Ronstadt’s excursions into the worlds of Gilbert and Sullivan and cabaret standards in the 1980’s had a similar effect.

But rock fans barely tolerate classical music adventures by the musicians they admire. Sir Paul’s fans snapped up his “Liverpool Oratorio,” “Standing Stone” and “Working Classical” albums out of curiosity or because they were completists, but you suspect that few who weren’t already interested in classical music actually play those discs. When Sir Paul presided over a program of his orchestral music at Carnegie Hall in 1997, the place was packed with people who sought a glimpse of him but who nodded off during the performances.

These crossovers tend not to do well from the other direction, either. Classical listeners find Billy Joel’s piano tinkling embarrassing and have been brutally critical of other musicians’ efforts as well. They may find it offensive that these musicians can get their baby steps recorded by major labels while trained, experienced, eloquent composers who don’t have rock affiliations have to pass the hat.

So here’s where rock stars enamored of classical music can make a difference. When they make their first classical albums, they might consider devoting their royalties – a pittance, compared with those generated by their other work – to a fund that would support recordings by actual classical composers.

“Yeah, right,” you say, but there is a precedent of sorts. In 1989, Elliott Carter received a telephone call from Phil Lesh, the bassist for the Grateful Dead. Mr. Carter had no idea what the Grateful Dead was, but when he and Mr. Lesh met, the following May, Mr. Lesh brought a stack of Mr. Carter’s music, which he knew intimately.

Mr. Lesh, it turned out, wanted to underwrite a recording of Mr. Carter’s music through the Grateful Dead’s Rex Foundation, which has quietly given grants to other composers as well.

Now that’s doing something useful. If Mr. Lesh wrote and recorded an opera, I’d happily give it a spin.

Ça Ira” released Tuesday, September 27 Roger Waters long awaited classical opera “ÇA IRA”is now in stores. .The lavish first edition of “Ça Ira,” an opera in three acts for full orchestra, soloists and choirs, will include a double SACD DigiPack and a deluxe 60 page four-color booklet including Roger Waters’ lyrics. As a bonus for Roger Waters fans, “Ça Ira” includes a special DVD documentary chronicling the “making of” the opera. The “Ça Ira” DVD traces the history of the project, from conception to completion, and includes revelatory interviews with Waters and the musicians and cast of “Ça Ira” as well as exclusive in-the-studio footage of the recording of the opera. Full information is now available on Roger’s official site.

Back in his days with Pink Floyd, Roger Waters took on the big issues of life. In high-concept projects like “The Dark Side of the Moon” and “The Wall,” he grappled with such challenging topics as social oppression, the long shadows of war, the interplay of money and power, and the abuse of authority.

Since 1989, Waters wrestled with many of those same concerns in a genre new to him: opera. The result, “Ca Ira,” an opera set during the French Revolution, arrives in stores September 27 from Columbia/Sony BMG Masterworks.

Spread over two Super Audio CDs and accompanied by a “making of” DVD and a lavish 60-page booklet, the recording features an accomplished cast, including bass baritone Bryn Terfel, soprano Ying Huang and tenor Paul Groves.

The opera’s setting and themes were inspired by a libretto written for the French Revolution’s bicentennial by songwriter Etienne Roda-Gil and his wife, Nadine, who also created illustrations for their co-written text. (Some of those images are included in the booklet.) Introduced to the couple by a mutual friend, Waters took on the task of writing the music for the opera, whose characters include King Louis Capet, Marie Antoinette and the revolutionaries who changed the course of history.

“Eventually, though,” Waters recalls, “Sony urged me to use English instead of French, so I wrote an English version of Etienne and Nadine’s work, and then I felt compelled to expand on their original text. Their work was really a series of gorgeous tableaux, and I added more personal narrative and history for some of the characters.”

Waters’ music recalls the lush, hyper-Romantic sound of opera composers like Puccini. “(He is) definitely an inspiration,” concurs Waters, who also sees common ground between his rock compositions and some of Puccini’s work: “After all, his opera ‘Tosca’ takes place in a police state.”

It will not come as much surprise to Pink Floyd fans that “Ca Ira” contains a number of non-musical elements. Waters’ concept involves sound effects, a number of non-singing roles and staging inspired by the theatrical conceit of a three-ring circus. “All of this,” he concedes, “would be hugely expensive to mount.” As a result, the opera has yet to be staged live, though a concert performance is planned for November in Rome.

Waters sees strong parallels between the turbulence of the French Revolution and contemporary geopolitics.

“All my life,” muses Waters, whose father died in World War II, “I have been preoccupied with the great tragedy of losing family in wars. The pain of losing a parent or a child in (an act of) violence that is purposefully and directly generated by political forces is in a certain way harder to bear than if someone dies in, say, an accident. The death feels more preventable.” Reuters/Billboard