Princeton University hosts interdisciplinary conference devoted to the music of Pink Floyd, featuring the world premiere of Amused to Death 5.1 (Filed 22 April)

Introduction

Pink Floyd as a musical institution has engendered a great deal of cultural documentation as well as commentary and often contentious debate, and so it was heartening to me both as a fan and armchair Floydian historian/critic to witness enthusiastic participants coming together to experience another perspective of this type of activity, courtesy of Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight and Structure at Princeton University.

Pink Floyd as a musical institution has engendered a great deal of cultural documentation as well as commentary and often contentious debate, and so it was heartening to me both as a fan and armchair Floydian historian/critic to witness enthusiastic participants coming together to experience another perspective of this type of activity, courtesy of Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight and Structure at Princeton University.

As I noted in my event preview for AFG, “The Liberal Arts of Pink Floyd,” this was the first-ever academic conference devoted to the band’s work with a specific interdisciplinary focus which is wholly appropriate given the band’s artistic agenda and presentation throughout their career. Pink Floyd is a band which encompassed different forms towards a unifying statement, and long-time fans understand how important it is to give equal credit to every part of the whole.

The event was also a unique success in regards to a programming exclusive: the participation of award-winning producer/engineer and Floydian associate James Guthrie meant that the inclusion of a 5.1 demonstration of Pink Floyd music would ensure not only the highest-quality standards of presentation, but also a world premiere: the 5.1 mix of Roger Waters’ landmark 1992 album Amused to Death, which will be released later this year on hybrid SACD by independent audiophile distributor Acoustic Sounds on their Analogue Productions imprint.

The events began on April 10th with a gathering at local cafe Small World Coffee. “If We All Pull Together” was an Floydian jam session with participants of the conference as well as open to any attendees who desired to participate. The evening of April 11th saw an airing of Pink Floyd The Wall at Taplin Auditorium, sponsored by the Princeton Film Society. The cinematic adaptation of the band’s 1979 concept album, directed by Alan Parker, written by Roger Waters and featuring the animation art of Gerald Scarfe, it has been praised by such critics as Roger Ebert, who noted in a review published in 2010, “the 1982 film is without question the best of all serious fiction films devoted to rock.“ The conference’s guest of honor, James Guthrie, was awarded a BAFTA for Excellence in the Craft of Sound in 1982 for his mix of the music, which comprises nearly the whole of the film’s soundtrack.

McAlpin Hall was alive with the sounds of Floyd on April 12th during the afternoon and evening as two playback sessions were held featuring the Surround Sound mixes of the classic albums The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here as well as Amused to Death, an album specifically crafted for the immersive experience of Surround Sound audio, and thus a welcome addition to the 5.1 pantheon.

The conference itself took place on April 13th at Taplin Auditorium and McCosh Hall, with a full schedule of music, presentations and discussion. What follows is my chronicle of the events of Saturday and Sunday, as having to travel from sunny San Diego precluded my involvement in all of the events, but as the experience in total was planned and executed with such obvious passion and enthusiasm by co-coordinators Gilad Cohen and Dave Molk – both PhD candidates in Composition at Princeton – all parts contributed to the overall success of the conference’s goal: to provide both intellectual and emotional stimulation and further appreciation of the work of a band wholly unique both in musical and popular culture history, an artistic entity with a singular vision which created an impression that continues to resonate with fans and fellow artists in the present day.

text: Julie Skaggs

Part One

April 12th: You’re surrounded (by Pink Floyd)!

World premiere of Amused to Death 5.1 and 5.1 demonstrations of The Dark Side of the Moon & Wish You Were Here

McAlpin Hall, 3:00 pm – 10:30pm

This event was – in my estimation – the true coup of the programming, as James Guthrie believed that a conference devoted to the music of Pink Floyd should, in fact, contain the actual recordings of the band, and so an enormous amount of planning and negotiation went into the logistics of this day. Guthrie and his team, comprised of das boot recording engineer Joel Plante, Gus Skinas of Super Audio Center (an acknowledged industry expert in DSD/SACD technology), Charlie Bolois of Vertigo Recording Services (vintage equipment guru to the stars and ATC Loudspeakers specialist on the West Coast) and Chad Kassem of Acoustic Sounds, Inc. spent nearly two days on the room treatment and setup for the playback sessions. Each session would comprise an airing of each recording, with a seating configuration designed for maximum effect (although overflow seating in the back would also be filled, as well as people standing on the sidelines and sitting on the floor). I was fortunate enough to be allowed to observe the final setup and testing prior to the first playback and so for a couple hours watched the master at work, as Guthrie ran pink noise and various ATD tracks from a position in the “sweet spot” at the center of the seating configuration, his professional acumen focused on getting the levels and balance just right; as well as last-minute tweaks to the room treatment and the creation of ambiance (or as they call it in recording studio parlance, “the vibe,” something which, as a producer, he is expertly adept in) including the appropriate placement of a lava lamp atop the center channel speaker at the head of the room and fabrics draped across speaker stands and other surfaces. He kindly invited me to sit behind him as he played the ATD track “Three Wishes” in its entirety and I was enveloped by the gorgeous textures of the new mix (more on that later, of course). Ever the perfectionist, his minute adjustments continued until almost the last minute, he then quickly slipped on his signature black blazer and gathered his notes, ready to move into presenter mode.

This event was – in my estimation – the true coup of the programming, as James Guthrie believed that a conference devoted to the music of Pink Floyd should, in fact, contain the actual recordings of the band, and so an enormous amount of planning and negotiation went into the logistics of this day. Guthrie and his team, comprised of das boot recording engineer Joel Plante, Gus Skinas of Super Audio Center (an acknowledged industry expert in DSD/SACD technology), Charlie Bolois of Vertigo Recording Services (vintage equipment guru to the stars and ATC Loudspeakers specialist on the West Coast) and Chad Kassem of Acoustic Sounds, Inc. spent nearly two days on the room treatment and setup for the playback sessions. Each session would comprise an airing of each recording, with a seating configuration designed for maximum effect (although overflow seating in the back would also be filled, as well as people standing on the sidelines and sitting on the floor). I was fortunate enough to be allowed to observe the final setup and testing prior to the first playback and so for a couple hours watched the master at work, as Guthrie ran pink noise and various ATD tracks from a position in the “sweet spot” at the center of the seating configuration, his professional acumen focused on getting the levels and balance just right; as well as last-minute tweaks to the room treatment and the creation of ambiance (or as they call it in recording studio parlance, “the vibe,” something which, as a producer, he is expertly adept in) including the appropriate placement of a lava lamp atop the center channel speaker at the head of the room and fabrics draped across speaker stands and other surfaces. He kindly invited me to sit behind him as he played the ATD track “Three Wishes” in its entirety and I was enveloped by the gorgeous textures of the new mix (more on that later, of course). Ever the perfectionist, his minute adjustments continued until almost the last minute, he then quickly slipped on his signature black blazer and gathered his notes, ready to move into presenter mode.

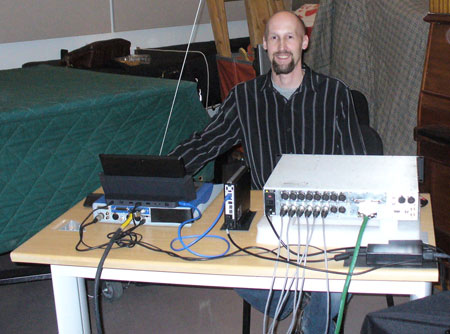

As both the professional audiophile press and general public filled the room and claimed seats anywhere they could, Guthrie’s introduction for ATD was given from behind the “command center” where Joel Plante manned a portable SADiE workstation. As the 5.1 mix of Amused to Death has not yet been mastered and authored for DSD, the source was a hard drive plugged into the DAW provided by Prism Sound. The monitoring – as had been advertised – was the same ATC setup which Guthrie uses at his studio, allowing the audience to experience these mixes the same way in which he hears them during their creation. ATC loudspeakers are an industry benchmark of excellence: installed in hundreds of professional audio facilities around the world as well coveted by consumers of high-end audiophile systems, and the sound is like nothing you will ever hear, the immediacy and clarity is truly amazing. I know I will never be able to afford such sonic luxury for my own home setup, so I am thankful Guthrie occasionally allows us to experience how the other half hears.

As both the professional audiophile press and general public filled the room and claimed seats anywhere they could, Guthrie’s introduction for ATD was given from behind the “command center” where Joel Plante manned a portable SADiE workstation. As the 5.1 mix of Amused to Death has not yet been mastered and authored for DSD, the source was a hard drive plugged into the DAW provided by Prism Sound. The monitoring – as had been advertised – was the same ATC setup which Guthrie uses at his studio, allowing the audience to experience these mixes the same way in which he hears them during their creation. ATC loudspeakers are an industry benchmark of excellence: installed in hundreds of professional audio facilities around the world as well coveted by consumers of high-end audiophile systems, and the sound is like nothing you will ever hear, the immediacy and clarity is truly amazing. I know I will never be able to afford such sonic luxury for my own home setup, so I am thankful Guthrie occasionally allows us to experience how the other half hears.

Guthrie elaborated upon the history of the production of Amused to Death – both its original recording and the new mix which we were about to hear – acknowledging that while it was a passion project of his own, part of the impetus came from fandom reaction at the initial announcement of the SACD release in January 2013, with many immediately lamenting as to the lack of a 5.1 mix for an album obviously years ahead of its time in the utilization of the immersive experience. Guthrie pleaded his case for a new mix directly to Roger Waters, stating plainly that this was not a project destined to turn a profit but rather should be viewed as an investment in a piece of art, as both men have often stated their admiration for the artistic accomplishments of the album. But even with Waters’ blessing such an undertaking would prove to be enormously challenging beginning with finding the multitracks. As Guthrie always creates a 5.1 mix directly from the multitracks it was absolutely essential that every piece of tape be found. He joked that employees and colleagues at British Grove, the studio in London where he began assemblage and review, frequently looked upon his labors with a “rather you than me” expression. The album was written and recorded over a five-year period at numerous studios with various sources including both 24 and 48-track analog as well as digital (for overdubs which were recorded years after the basic tracks of any particular song) and so not only finding every recording but then figuring out how they all fit together was daunting. The original album took shape with the mix – an incredibly complex interweaving of voices, music and ambient elements of many kinds – and so extreme care to recreate this intricate tapestry was rendered with the utmost respect for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Guthrie elaborated upon the history of the production of Amused to Death – both its original recording and the new mix which we were about to hear – acknowledging that while it was a passion project of his own, part of the impetus came from fandom reaction at the initial announcement of the SACD release in January 2013, with many immediately lamenting as to the lack of a 5.1 mix for an album obviously years ahead of its time in the utilization of the immersive experience. Guthrie pleaded his case for a new mix directly to Roger Waters, stating plainly that this was not a project destined to turn a profit but rather should be viewed as an investment in a piece of art, as both men have often stated their admiration for the artistic accomplishments of the album. But even with Waters’ blessing such an undertaking would prove to be enormously challenging beginning with finding the multitracks. As Guthrie always creates a 5.1 mix directly from the multitracks it was absolutely essential that every piece of tape be found. He joked that employees and colleagues at British Grove, the studio in London where he began assemblage and review, frequently looked upon his labors with a “rather you than me” expression. The album was written and recorded over a five-year period at numerous studios with various sources including both 24 and 48-track analog as well as digital (for overdubs which were recorded years after the basic tracks of any particular song) and so not only finding every recording but then figuring out how they all fit together was daunting. The original album took shape with the mix – an incredibly complex interweaving of voices, music and ambient elements of many kinds – and so extreme care to recreate this intricate tapestry was rendered with the utmost respect for the integrity of the work as a whole.

After listing the various guest contributions on the album, Guthrie’s summation was humorous and heartfelt: “…and you’ve got Roger singing his ass off.” Mindful of the artistic import and sonic complexity of the album, it’s no wonder it was high on his wishlist of 5.1 archival projects. For those who are fans of this recording and excited to finally experience it in high-resolution, we have two people to thank: Roger Waters for saying yes, and James Guthrie for his tireless focus and determination over a year’s worth of work, and appropriate reverence in restoring a classic for the ages.

After listing the various guest contributions on the album, Guthrie’s summation was humorous and heartfelt: “…and you’ve got Roger singing his ass off.” Mindful of the artistic import and sonic complexity of the album, it’s no wonder it was high on his wishlist of 5.1 archival projects. For those who are fans of this recording and excited to finally experience it in high-resolution, we have two people to thank: Roger Waters for saying yes, and James Guthrie for his tireless focus and determination over a year’s worth of work, and appropriate reverence in restoring a classic for the ages.

As professional-calibre 5.1 demonstrations of The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here have only occurred once each previously – DSotM in New York in 2003 and WYWH in Denver in 2011 – it was cause for celebration for the opportunity to experience these surround mixes as part of this event. As I had not been able to attend the DSotM 5.1 premiere in 2003 I was thrilled to finally hear the award-winning mix the way it was meant to be heard, and bask in the artistry and ambiance of classic Floyd.

All photos above show James Guthrie performing final testing and adjustments for the 5.1 playback in McAlpin Hall, with the assistance of Joel Plante and Gus Skinas.

text: Julie Skaggs

photos: David Kelly Crow & Julie Skaggs

End of Part 1

Part Two

Amused to Death 5.1: a review

James Guthrie provides an introduction to the second playback of Amused to Death 5.1 at McAlpin Hall.

The 5.1 aspect of this project has been an open secret since November of last year when, during the taping of an interview entitled Speak Easy: An Intimate Conversation between Roger Waters and Bill Weir, Waters revealed that the re-release of Amused to Death would also include a new Surround Sound mix, and the news was leaked by fans in attendance; but fandom response did not seriously ramp up until the announcement of the world premiere was made by the conference organizers a week before the event, followed up by an official announcement from Acoustic Sounds. But many have placed their pre-orders, gratified their desire has been fulfilled.

Upon its initial release in September 1992 the album was touted as “a movie for the mind” given its dynamic and involving arrangements and mix, featuring dozens of discrete sound elements interwoven within the songs and enhancing not only the overarching concept and narrative of the work, but also creating the world in which it exists. As listeners we experience the message of the album much the same way in which we experience the media empire which Waters was criticizing and commenting upon: a disturbing distraction always attempting intrusion. Yet underneath lay the most compelling compositions of Waters’ solo career, a collection which illustrates the depth and breadth of his artistic ambitions.

Remixes of classic albums are often the subject of debate in regards to historical perspective and continuity, but anyone acquainted with Guthrie’s efforts in the archival realm should already know that his priority is always the inherent integrity of the music both as form and art. There are many details which will delight the ears of long-time listeners as enhancements and even surprises, but nothing detracts or distracts from this album’s enduring status as a landmark recording; perhaps the best definition, post-1983, of Floydian in its expression of immersive narrative and astute social commentary. If anything, it is a perfect reminder of Roger’s overall aesthetic, writ on a global scale concerning themes and questions in the hearts and minds of all humans. The considerations of power and parity, of amusement and avarice, of devastation and delirium – it is all there within Amused to Death in layers of honesty, humor, and emotional nuance. The 5.1 mix reveals this widescreen story with its cast of thousands in breathtaking clarity.

As the setting is established with the first ambient aspects introducing “The Ballad of Bill Hubbard,” the clarity is immediate, with the reference field of 5.1 allowing for greater detail of elements and textures. As with any Guthrie mix, one can immediately apprehend and appreciate the discrete elements as well as the musical continuity they reside within in a concurrent fashion. Recalling the use of the barking dog as a reference point for stereo polarity in the original mix (the album credits contain the notice: If the dog barking at the beginning of the record doesn’t sound like he’s in the yard next door then your speakers are out of phase.), I closed my eyes and tried to imagine how far away it was now…further down the street, perhaps? My headspace felt much roomier when considering the placement of the SFX elements in the soundstage, although the aspects were where I expected them to be most of the time. Speaking voices are primarily behind one in the left channel which provided a distinct impression of internal rather than external commentary, as if we were truly meant to be inside the world Waters constructs…inside the television itself, even. As the instrumental atmosphere takes center stage, Jeff Beck’s guitar is very present as a separate voice and achieves this character throughout the mix itself. The effects which precede the testimony of Alf Razzell also seem much more direct while also fully integrated.

The first permutation of “What God Wants” is one of Roger’s iconic big rock anthems, and what is instantaneously apparent is how well this track swings, the “power of the groove” as Guthrie indicates in his keynote speech, is wholly present. And the little details are very rewarding to a close listener, such as when the stadium door swings open behind us and the air changes as the roar of the crowd swells, the tension building almost unbearably until the downbeat hits and is then released. Crisp accents and a rich low end providing a dynamic foundation which is also interactive with all of the other components is a hallmark of this new mix.

The first part of “Perfect Sense” features an augmentation familiar to fans who have seen Roger tour in the past decade…as Guthrie noted in his talk, the sample of the HAL 9000 from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey which had been denied previous use by Stanley Kubrick (possibly an answering salvo to Roger’s refusal to allow the director to use a Pink Floyd track in A Clockwork Orange) has been restored to its originally conceptualized place in the composition, as it certainly underscores the lyrical sentiment and thematic aims of the work as a whole. Beginning with this track there is a greater recognition of the intimacy of the vocals in the mix, the clarity of the details, and the dynamics of the arrangement. With the line the monkey looked up at the stars, the accompanying sound effect rises above our heads in emphasis of the imagery invoked. The amazing powerhouse of P.P. Arnold’s voice is warm and bright and the gospel-like intensity of the “global anthem” in the second part of the song is thrilling.

Engineer Joel Plante with the portable SADiE digital audio workstation provided by Prism Sound.

“The Bravery of Being Out of Range” also displays more warmth, nuance and groove in the new mix, while retaining the airiness of the “live” feel of its concept, especially in the waves of Hammond organ which wash across the reference field. “Late Home Tonight,” one of the centerpieces of the album in its thematic range and far-reaching ambition, emphasizing Roger’s preference for the uses of narrative in his songwriting, is positively epic in both parts with the portrayal of all the sonic accents interwoven into the beauty of the instrumentation and the grandeur of Michael Kamen’s orchestrations while also evoking a poignant mood. And if that bombing run doesn’t startle you even if you know it’s coming…then you might possibly be unconscious at the very least. These two tracks are also a wonderful example of how sound effects are used as percussive elements within the arrangement, something which is also a part of the DNA of The Final Cut.

“Too Much Rope” features many discrete elements and crossfades combined with wonderfully-rendered layering to provide one of the most obvious moments of 5.1 enjoyment. But they do not pull the listener out of the song, but rather enhance its message further and frame other elements such as Steve Lukather’s soaring blues-soaked guitar. Wandering across the dial once more into “What God Wants” that same intensity of groove and texture is immediate, sounding much more like a continuation than a reprise. Then as the third section emerges out of the night outside (which seems to surround us from all sides), with its obvious Floydian evocations of drama and humor, the mix imbues it with an emphasis befitting the mood.

In “Watching TV” I really seemed to notice the crispness and immediacy of the center channel, especially Roger’s vocal and Don Henley’s accompanying harmonies (and how the two seemed to switch places, so to speak, as the song progressed) as well as smiling at Andy Fairweather-Low on the talkback in the right rear channel and the wine glass textures at the beginning of the song.

“Three Wishes” is my favorite song on the album, with its’ beautifully complex textures and rich low end, the discrete elements and layering in the mix working together to underscore the groove. Jeff Beck’s bluesy voicings are equally as emotive as the other vocals and the coda is incredibly effective: dramatic and atmospheric. Having heard this song hundreds of times since the album’s original release, after hearing the 5.1 version during the pre-event setup I immediately felt like I couldn’t get enough of it, the new mix is just that amazing. Not markedly different, but uncovered somehow, like a painting which has been resorted to its true coloration. Luckily I got to hear it twice more during the playbacks (and twice total from the third-row center sweet spot).

The children’s voices which are a part of the introduction of “It’s A Miracle” provide a dynamic counterpoint to the other instruments, and there’s an emphasis on atmosphere, particularly in the texture of the organ, which ebbs and flows, with a beautiful interplay between the organ and piano, and a great drum track by Jeff Porcaro. The layers of Roger’s voice provide a sense of warmth and soul which is so effective in terms of his vocal style. There is a suitable dramatic transition in the coda, ending with the sounds of changing channels illustrating the juxtapositions of entertainment and information, a surreal example of the serious having to compete with the ridiculous.

The title track features what could be considered another unusual guest star in Roger’s overall musical history – this time Rita Coolidge – but her buttery soulful style is the perfect addition to the overall mood of the song. The mix’s emphasis on dynamics means the big moment hits hard and lifts the arrangement right out of its reflective mood into another anthemic interlude which carries through to the end. The recursive ending underscores the range of emotions we have experienced over the course of the album, a glimmer of hope that we might manage to stop ourselves from further ruin somehow, some way…by remembering the importance of human communication and cooperation.

As the final ambient elements faded away and I was released from that world Roger had created to tell the story, I found myself very happy to know that this masterwork has finally received the treatment it so richly deserves in its preservation and enhancement for all time. There is a reason why Guthrie is so well-known from a professional standpoint in the world of immersive audio experiences, and his 5.1 mix of Amused to Death is a master class as rendered by his taste and technique.

text: Julie Skaggs

photos: Julie Skaggs

End of Part 2

Part Three

April 13th: Floydian Appreciation 101

Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight and Structure conference

Taplin Auditorium, 10am – 4:15pm

In keeping with the theme of the conference, each of the five academic presentations addressed a different aspect of Pink Floyd’s artistic infrastructure, the elements of which combine to memorable effect. It’s often difficult not to lend a visual and/or literary aspect to Pink Floyd music, for example. The schedule also included renditions and reworkings of Pink Floyd compositions to illustrate the cornerstone of our shared interest.

The day’s program began with a duet from co-coordinator Gilad Cohen on acoustic guitar and vocalist Wally Gunn, performing “Pigs On The Wing (Part I)” from Animals, and as that particular album provided fans with one of the most enduring symbols of the band, it was an appropriate choice to introduce Troy Herion’s talk “The Visual Music of Pink Floyd.” His precis begins with a compelling rhetorical question: Is there any band more visually commanding than Pink Floyd? and any other band which has also employed visual continuity of presentation (such as Yes and Tool) certainly owe Pink Floyd a large debt of acknowledgement. Herion’s speciality (as a PhD candidate in the Composition program) is what he terms visual music and he touched on the definitions of such a methodology as well as the ways in which the band employed these aspects throughout their career in such expressions as live performance, album art, film, and audience-generated visuals (the appropriation of a band’s iconography through fan art, such as the vast amount of people sporting Pink Floyd-themed tattoos, for example). The use of sonic images by Pink Floyd to construct a musical space around a listener fortified by the consistent use of visual surrogates provides connections which then render those images forever connected to the music providing sonic stimulus. The band’s identity is so bound up in those visual cues that they then can be replicated by outside influences and still fully recall the mood and tone of the original experience. Herion pointed out that a great example of this phenomenon is attending a rock Laser Show featuring the band’s music; the use of lasers to accompany the music will provide the appropriate resonance which the visual identity of the band has already established. As fans, we instinctively perceive Pink Floyd in visual terms as strongly as the musical aspect.

The next musical interlude featured Gilad Cohen on piano and Brian Adamczyk on saxophone performing a arrangement of “Don’t Leave Me Now” from The Wall, and I found it very interesting that the ambience of the song still remained even when stripped down to two instruments, but the mood had changed given the choice of voicing – the sax lent an air of longing to a song which is normally spiked with black-hearted satire.

Co-coordinator Dave Molk’s presentation, “Space and Repetition in David Gilmour’s solos” invited the attendees to look at the Floyd’s music from a different perspective as the solos of David Gilmour were examined for both technical and emotional content. Molk began by asking the audience to name their favorite solo and why (mine is “Time,” in case you were wondering) and he then addressed the evolution of his style over time. acknowledging that Gilmour is a master of tone and also of space and the use of repetition to underscore thematic elements in the songs themselves, tracking the movements of chord progressions and motifs. Gilmour’s signature slide playing has also evolved throughout the Floyd’s discography and this was illustrated by listening to the solos in “One Of These Days” and “High Hopes.” We then listened to “Time,” one of his most famous solos, to apprehend why it is so iconic. Molk’s explanation of the overall structure allowed us to find the similarities within Gilmour’s pick-type and slide solo work, and upon hearing it again it was very easy to discover those memorable elements which mark Gilmour’s genius in his work as a whole.

Molk’s sonic reworking, “A Medley Full Of Hits,” performed by PUBLIQuartet with Gilad Cohen on piano, created a fun guessing game of “spot the song,” and was not quite as easy as one might think, with the interesting perspective of string quartet and piano performance.

After a short tea break, the last part of session one featured Professor Nigel Smith’s presentation “Several Species of Small Furry Animals: The Genius of Early Floyd” wherein Smith reclaimed the glory days of post-Syd/pre-Dark Side Floyd, which is often overlooked in cultural criticism. Smith reminisced upon his years as a Floyd fan in the London area in the early 1970s and the band’s impact upon the cultural landscape of the time, as well as the indelible mark left upon his own musical apprehension. At the time, the emphasis was upon the symbiosis of a group collaborative effort, which informed the Floyd’s artistic output, creating a sound which can only be found in that particular period of their history – from Saucerful to Meddle – as well as an emphasis on idyllic, pastoral, deeply emotional music as an expression of the idealism of Albion. The band’s place of origin was very important in their artistic evolution, and especially the way in which their compositions could grow and change with live performance honing the songs before they came to be recorded in their final form, underscoring the relationship the band had with their audience as serious listeners (which, as most long-time fans know, would change with the near-overwhelming popularity of The Dark Side of the Moon).

Ryan Sarno’s re-imagining of “Echoes” – titled “Two Separate Glances” – was performed by his group Sant Saens Seine featuring Sarno on electric guitar and Megan Conlon and Yanie Fecu on vocals. The seemingly strange angularity of Sarno’s guitar playing was a wonderful surprise, providing an interesting counterpoint to the harmony, as the arrangement rose into the figurative clouds in much the same way as the original, just by way of a different route.

When the attendees reassembled after lunch for session two, Sarno also returned for his presentation, “They Fluttered Behind You: The Past as Material Object in Pink Floyd,” which he described as “the codification of the past in the post-Barrett era Pink Floyd.” He began with a discussion of the concept of time as portrayed in the band’s oeuvre, framed by the overall aesthetic agenda of the two eras, with the Syd-led Floyd featuring an original and idiosyncratic identity and the use of improvisation. A movement towards structure marked the post-Syd era, with a progression from the eternal to the fixed temporal, and the uses of the studio as compositional device rather than live performance. Both musically and lyrically the themes are recursive and thematically there are equally important distinctions which of themselves are differently expressed and emphasized.

PUBLIQuartet returned to the stage to perform Quinn Collins’ re-imagining of the Syd-era classic “Interstellar Overdrive” for the 21st century, “NTRSTLR OVRDRV,” which was just as mindbending as rendered by an electric string quartet (including the use of trippy feedback…too bad we couldn’t have also had a liquid light show to accompany it).

The final presentation came from Gilad Cohen, an examination of Pink Floyd’s most elegiac composition: “The Shadow of Yesterday’s Triumph: ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ and the Stage Theory of Grief.” In acknowledgement of the deep and wide emotional range of SOYCD both lyrically and musically, Cohen reiterated what we know of Floydian history in regards to the song: a tribute from the Floyd to their fallen comrade Roger “Syd” Barrett, expressing their regret and guilt in regards to Barrett’s mental unravelling which ultimately led to his withdrawing not only from the band, but also the music industry and society at large. Cohen explained the structure of the stage theory of grief, stating there are five stages: numbness, yearning, anger, mourning, and acceptance. He provided an analysis of the structure of the song in regards to these stages, speaking specifically to the main motifs and dynamic movement of the arrangement. For example, the largely ambient section at the beginning of the song, which goes on for nearly four minutes, can be categorized as the numbness which marks one’s emotions in the beginning stages of grief. And the lap steel solo in Part VI is an expression of anger in its intensity of presentation. Cohen called frequent attention to the importance of chord progressions and other elements by demonstrating on either acoustic guitar or piano, and injected humor, reverence, and erudition into his presentation, imbued with natural charisma and passion for his subject, and the audience rewarded him by breaking into applause several times before the conclusion of his talk.

To conclude session two, PUBLIQuartet and Cohen on piano were joined by Hilary Jones on flute and Brian Adamczyk on clarinet for Cohen’s arrangement of “Shine On” which definitely resonated with a room full of people who had spent nearly an hour considering the genius of this song and was both beautiful and unique in its presentation.

text: Julie Skaggs

photos: David Kelly Crow

End of Part 3

Part Four

“The words ‘that’ll do’ are not really in my vocabulary.”

James Guthrie keynote address and panel discussion/Q&A

McCosh Hall, 5pm – 7pm

James Guthrie delivering his keynote speech at McCosh Hall, Princeton.

Obviously the biggest draw as well as the legitimacy factor in terms of fandom credibility was in securing James Guthrie’s participation for this event. As someone who prefers to remain behind-the-scenes and within the bucolic environs of his own studio, Guthrie is not one to readily grant interviews, let alone requests for public appearances. It is to the credit of the organizers that they acknowledged any examination of the sound of Pink Floyd should include the perspective of the man who serves as “the keeper of the audio flame,” as Jon Carin, a fellow Floydian associate, once characterized Guthrie’s role in the organization. The primary reason why Pink Floyd enjoy a reputation for having one of the best-sounding and well-maintained back catalogs of any popular band is illustrated in his dedication and eternal perfectionism.

I first encountered that motto of Guthrie’s – which was included in his keynote address – back in 2009, he used it to describe his perfectionist stance in the early days of his career, and in considering the whole of his employment – not just as the Floyd’s preferred sonic architect – it seems a wholly appropriate way to summate his exacting standards and laser-like focus upon the smallest of details. He is a master craftsman who is also wonderfully inventive and creative in all aspects of his career: from the technical side as recordist, mixer and mastering engineer, to his work as a producer, arranger, and musician.

But Guthrie’s keynote address, while ostensibly focusing on the subject of recording and production techniques he has utilized throughout his 40-year career, also contained ample amounts of humor, intelligence and passion for his profession and its end result: recorded music which is built to last, to transcend trends and time itself. Much of the work he has been a part of is timeless and enduring – any sampling of pop/rock radio within a given day is likely to yield several hits which feature his engineering, mix and/or production contributions; not just Pink Floyd , but also artists such as Heatwave, Kate Bush, the Pointer Sisters, Ambrosia and Toto.

Guthrie began with differentiating the types of recording – live and studio – as well as particular approaches to projects, noting that Pink Floyd’s creative process tended to occur in the studio. He described the role of the producer in a project, someone who serves the artist by creating a safe environment (especially for singers, who need to be able to trust the people on the other side of the glass), capturing the performances, and sometimes tricking the performers into being spontaneous in order to achieve the best result. He then moved into the more specific realm of working with the Floyd, wryly quipping, “Most albums evolve…particularly Pink Floyd records.” He discussed the making of The Wall, which he said took shape in the mixing (which he helmed at Producers Workshop in Los Angeles), noting that through the crossfades and sequencing of the tracks, the narrative began to emerge like the movie it would later become.

After delivering one piece of advice to future producers: “Never underestimate the power of the groove,” Guthrie related what is one of the more infamous Pink Floyd recording tales, usually referred to as the “I must not fuck sheep” story. Also reprised by him in Nick Mason’s 2004 book Inside Out, it relates a contentious day during the recording of The Final Cut at Roger Waters’ then-studio The Billiard Room, and co-producer/orchestral arranger Michael Kamen’s struggle with focus which took hilarious form, especially as related via Guthrie’s dry English wit. Noting that humor is very important in the process of recording an album, other classic funny stories were related, including Nick Mason’s assessment of his own drumming abilities during the re-recording of “Money” for A Collection of Great Dance Songs (“I was always much better at the after-gig parties.”), a prank involving a mix of the live version of “Learning To Fly” from PULSE which led co-producer David Gilmour to remark he wished he’d used it on the original recording, recording Roger’s backward scream over the phone while his family looked on in confusion, the iconic phone call which concludes “Young Lust” (which Guthrie was responsible for, although he edited his own voice out of the finished track), and the comedic but also near-disastrous “Hold it!” story from the opening night of The Wall performances at the Los Angeles Sports Arena in February 1980 (these last three anecdotes can also be found in Vernon Fitch’s book about the creation of The Wall album and stage shows, Comfortably Numb). Guthrie also described his first day on the job in October 1973 at age 19 as a trainee tape operator at Mayfair Studios in London and how he found himself “thrown into the deep end” by having to work a session with a stern warning from his new employer (“Just do exactly what I tell you to do, as fast as you can.”). He commented that he felt fortunate to have entered his profession in the analog era, which afforded the greatest opportunities for creative problem-solving and discoveries.

James Guthrie answers a question from the audience during the panel discussion at McCosh Hall.

(L to R: Troy Herion, Ryan Sarno, Nigel Smith, Dave Molk, James Guthrie and Gilad Cohen)

Guthrie also delivered time-tested pieces of production wisdom, such as “be ruthless” by not allowing yourself to become too attached to any one element of a song, as well as “broaden the color palette” by using different types of gear and spaces. And perhaps the most important: “learn how to listen, then learn to trust your ears” rather than relying on waveforms and meters to give you all your sonic information. But his penultimate sentiment extends beyond the processes of recording: passion and creativity enhance not only one’s work, but life itself.

After thunderous applause and cheers for the man of the hour, the panel discussion began with an introduction from moderator Shaugn O’Donnell, speaking on the seeming gap between the popular apprehension of Pink Floyd and their lack of recognition within academia, which the band may have inadvertently contributed to themselves. He provided humorous-in-hindsight moments in regards to critical opinions during the band’s beginnings which were often dismissive and even insulting. But O’Donnell aptly illustrated that the band’s artistic evolution and legacy belong just as equally within an intellectual perspective as a popular one. The Q&A session which followed was mostly comprised of questions from the audience for Guthrie regarding past and future projects. When it was my turn I commented to the panel that they were sitting on stage with the man who likely best knew the definition of Floydian and so I wanted to know how each of them would define the term. The answers were varied and fascinating in their specific differences, and O’Donnell later thanked me for what he felt was the best question of the Q&A.

The conference – and the weekend – drew to a close with a performance of “Pigs On The Wing (Part II)” – performed as with Part I by Gilad Cohen and Wally Gunn – in an aptly recursive loop (now there’s one of the definitions of Floydian, I’d say) and as members of the audience gathered around the Guest of Honor for comments and autographs and photos I felt a distinct void…because really, how many chances does one get to talk about Pink Floyd all day to actual people? In my opinion, not nearly enough of them, and that’s why I loved this event. As always with our shared passions, enthusiasm carries the day and establishes the connections we crave. To know that the music of Pink Floyd is responsible for creating enduring curiosity and community is perhaps the greatest element of their legacy indeed.

Special Thanks

Gilad Cohen, Dave Molk, Ryan Sarno, James and Melissa Guthrie, Charlie Bolois and Lori Sortino, Joel Plante, Gus Skinas, Chad Kassem, John Jackson, Jon Carin, and Alan Green (also many many thanks to Col Turner and David Mikkelson and tremendous gratitude to David Kelly Crow for the use of his excellent photos)

And in conclusion…

The author would like to request that anyone who attended the conference and found new reasons to admire James Guthrie…please read his Wikipedia entry – which she has solely researched, composed and updated over a number of years – to learn even more about his illustrious and wide-ranging career as one of the most respected producer/engineers in the industry.

L to R: Troy Herion, Gilad Cohen, Nigel Smith, James Guthrie. Shaugn O’Donnell, Dave Molk & Ryan Sarno

photo by David Kelly Crow

text: Julie Skaggs

photos: David Kelly Crow & Julie Skaggs

End of Part 4

Thank You!

AFG wishes to express our appreciation to Julie Skaggs for this wonderful series of reports (Julie, you are a superstar!) and a big AFG Thank You to Gilad Cohen and Dave Molk for planning and organizing this amazing event.