For the last couple of years, it has been tradition for Nick Mason and his wife Annete to host an open garden event at his very historic Middlewick House estate.

For the last couple of years, it has been tradition for Nick Mason and his wife Annete to host an open garden event at his very historic Middlewick House estate.

The event will take place on June 3 and 4, 2023, and will include plants for sale, stalls to browse, and farm animals to see. Tea, coffee, cakes, and a selection of food stalls, from BBQ to smoked salmon, are available throughout the day.

The event is all in aid of charity, and with Roger Waters’ This Is Not A Drill European Tour 2023 arriving in the UK around the same time, it’s the perfect way to round off a month of Floydian related activities.

More information and tickets are available by visiting – https://middlewickhouseopengarden.com/

Our compadres over at Pink Floyd Collectors have just brought to light an interesting revelation from the latest book, ‘Through the Prism,” by Pink Floyd Art Director Aubrey Powell

Our compadres over at Pink Floyd Collectors have just brought to light an interesting revelation from the latest book, ‘Through the Prism,” by Pink Floyd Art Director Aubrey Powell

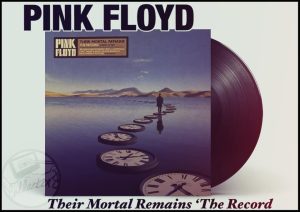

Due to popular demand the Official Pink Floyd : Their Mortal Remains Exhibition Montreal has been extended, In a statement released today

Due to popular demand the Official Pink Floyd : Their Mortal Remains Exhibition Montreal has been extended, In a statement released today Durga McBroom, best known for her work as backing vocalist / collaborator for Pink Floyd (between 1987 – 2014), is featured as the guest star on the upcoming single and album by Finnish prog rock group 5th Season. The single ‘Desparate Measures’ will be out on streaming platforms on November 4th and the album early in 2023.

Durga McBroom, best known for her work as backing vocalist / collaborator for Pink Floyd (between 1987 – 2014), is featured as the guest star on the upcoming single and album by Finnish prog rock group 5th Season. The single ‘Desparate Measures’ will be out on streaming platforms on November 4th and the album early in 2023.

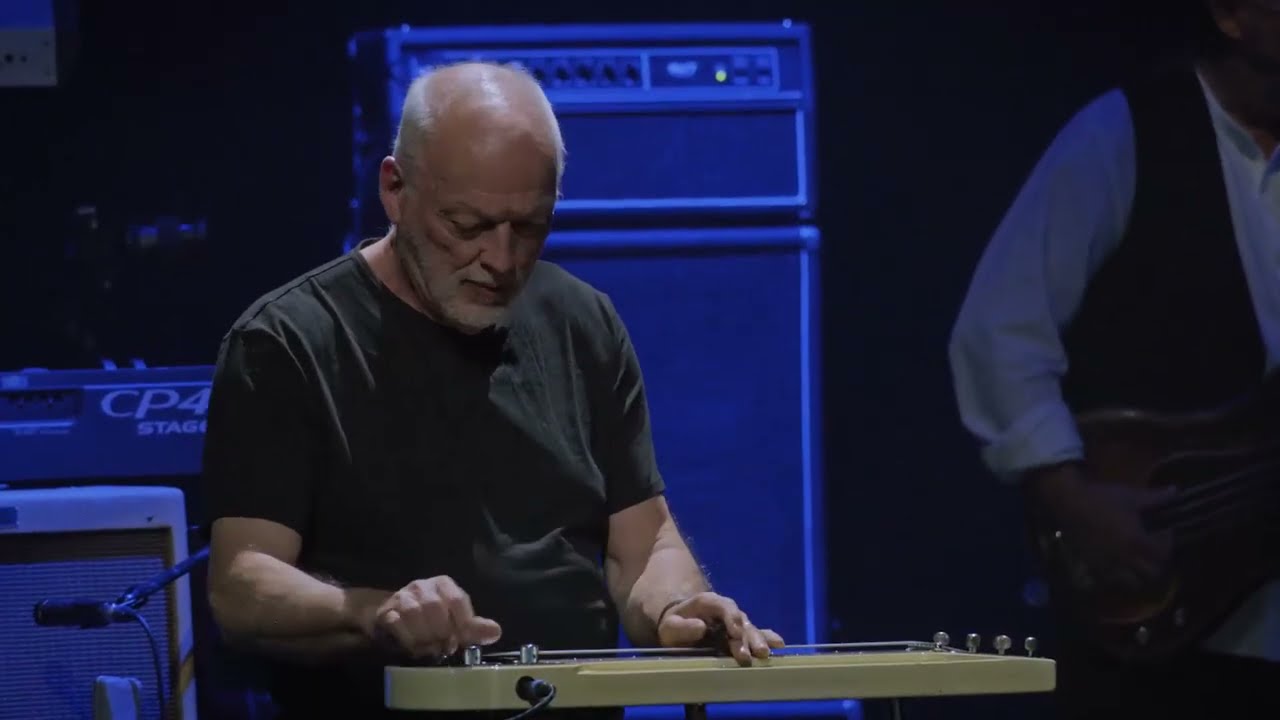

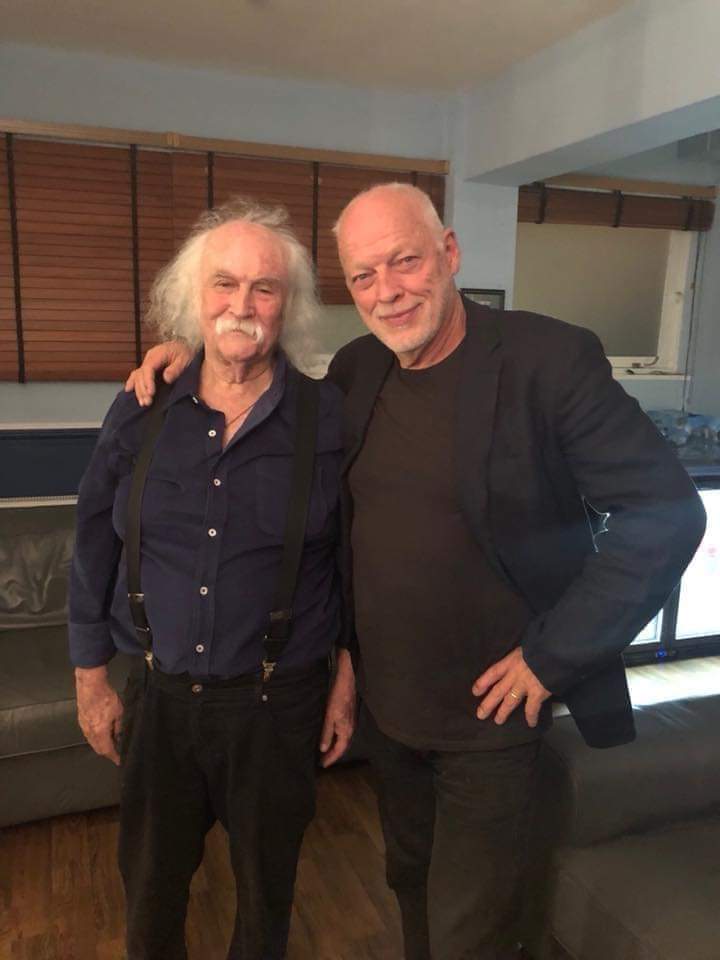

We are very sad to break the news that David Crosby has tragically passed away.

We are very sad to break the news that David Crosby has tragically passed away.