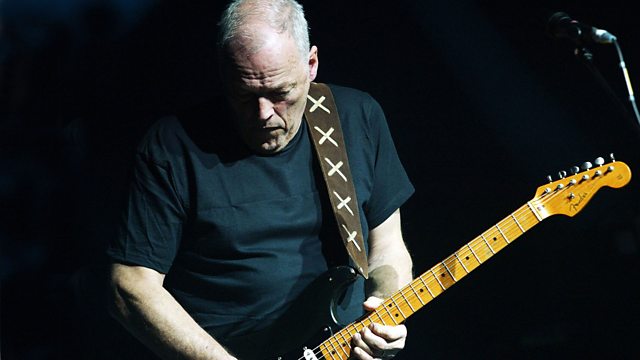

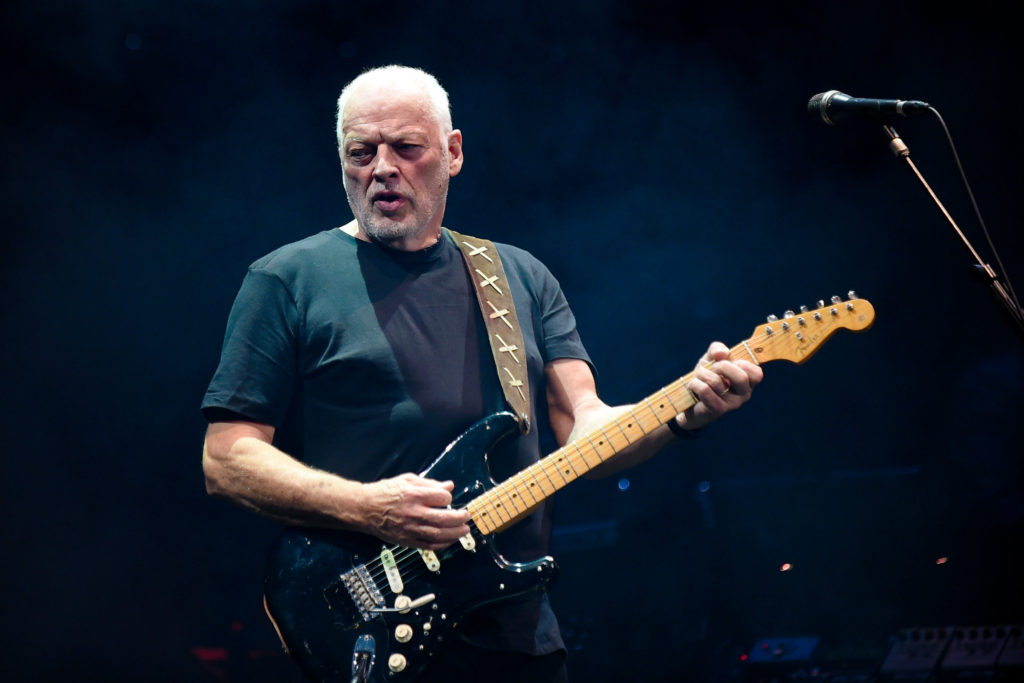

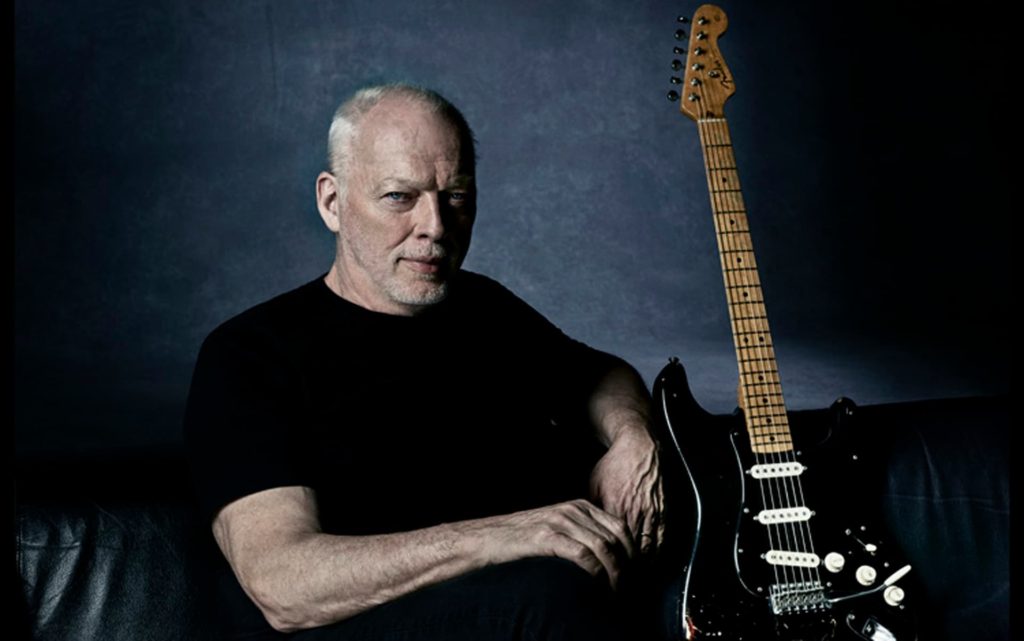

More than half a century after he joined Pink Floyd, David Gilmour will be auctioning off about 120 of the iconic guitars he played both with the band and on his solo releases. “Everything has got to go,” he jokes. “It’s the spring sale.”

More than half a century after he joined Pink Floyd, David Gilmour will be auctioning off about 120 of the iconic guitars he played both with the band and on his solo releases. “Everything has got to go,” he jokes. “It’s the spring sale.”

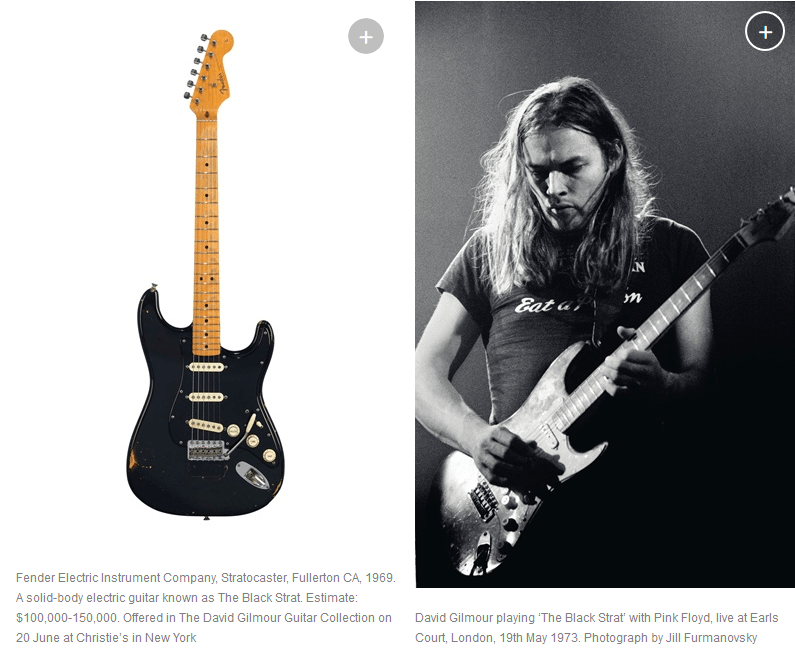

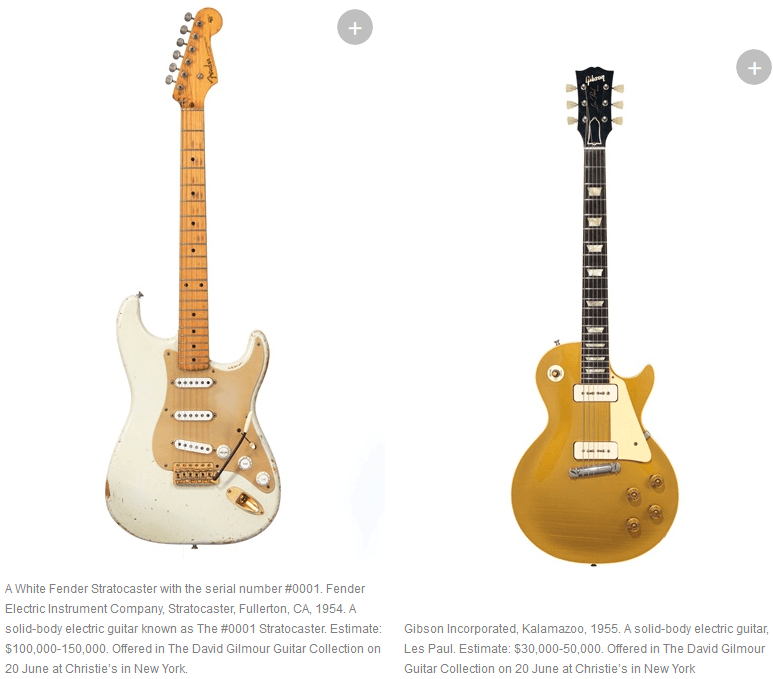

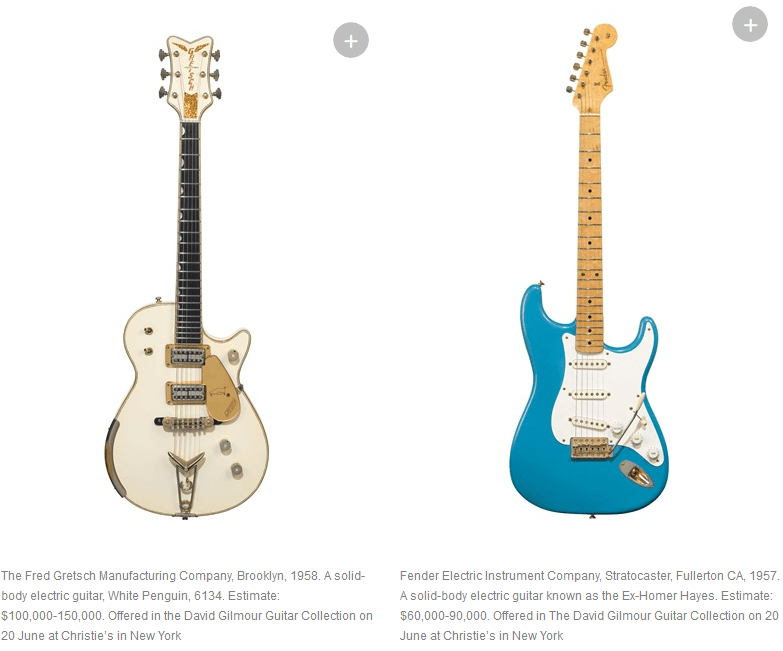

The instruments that will be on the auction block at Christie’s New York headquarters this June include many of his signature instruments. He’ll be selling the Black Strat — a guitar he played on “Money,” “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” and “Comfortably Numb” and enough other songs that it has amassed a legacy worthy of its own book — as well as his Stratocaster with the serial number 0001, the 12-string he wrote “Wish You Were Here” on and the Ovation six-string he’s played “Comfortably Numb” on at almost every live performance he’s done.

“These guitars have been very good to me,” he tells Rolling Stone on a phone call from his home in England. “They’re my friends. They have given me lots of music. I just think it’s time that they went off and served someone else. I have had my time with them. And of course the money that they will raise will do an enormous amount of good in the world, and that is my intention.”

The auction’s proceeds will benefit Gilmour’s charitable foundation, which he’s been running for decades. “The money will be going to the larger needs of famine relief, homelessness and displacement of people throughout the world,” Gilmour says, adding that the charities are both global and U.K.-centric. “We are going to work on the best way and the best balance of making what this raises do as much good on this planet as it can.”

In addition to helping out those less fortunate than him, Gilmour sees the sale as a matter of cleaning house. In fact, he’s been planning on selling of chunks of his collection since at least around 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason but hasn’t gotten around to it. “I didn’t want to get too ancient and have a whole stash of guitars sitting around doing nothing,” he says. “And frankly, too many of them are guitars I just don’t have time to play often enough. They will give joy to other people.”

What sparked the idea to sell these guitars? Were you just looking around a room and you thought, “There are too many of them”?

This is something that’s been creeping up on me for quite a long time. I started a process before, and I’ve ducked out a couple of times. This time, it is going to happen. I’m both sad with losing some of the instruments and relieved to get this thing dealt with and that it will be doing some good. If I need a particular guitar, I’ll go out and buy another one. They are the tools of my trade. They have given me music, but in the end, they are the tools that I use.

You’re selling around 120 guitars. What percentage of your collection is that?

To be honest, I don’t know. There are a few remaining. There are some that I am going to hang onto, either because they have been duplicated or because they are ones that I can’t physically bear to part with. So I guess I’ll probably be keeping 20 guitars.

I take it you’re not superstitious about having “the right guitar” for a certain song?

Guitars are special in what they give you, but I’m not overly sentimental about the qualities that some people think become imbued in one particular instrument itself. The guitars that I play on a lot tend to be the ones that are closest.

Let’s talk about the Black Strat. That has to be a hard one to say goodbye to.

You know something? For me, I can let go of it. It’s going to bring a lot of people to have a look at this sale, and it’s going to do that job. It’s a lovely guitar. It has been on pretty much all the Pink Floyd albums through the Seventies. It’s on Meddle, Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals, The Wall. I did my “Comfortably Numb” solo on it. The notes for the beginning of “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” fell out of it one day. It’s on so much stuff, but Fender have made replica ones that they sell, and I have two or three of those that are absolutely perfect. One of those might be my future guitar of choice or even, horror of horror, maybe I’ll even change the color.

What is the history of the Black Strat?

It’s a 1969 Strat, which I bought at Manny’s on 48th Street in New York in 1970. I have done dozens of modifications to it. I’ve changed the neck a couple of times. I’ve drilled holes in it and done all sorts of weird things to it. But the color is the one thing I’ve never changed. It was always black.

Since you modified it so much, when did you get the sound out of it that you wanted?

I change it then I change it back. I added a little switch in it so I could get a pickup configuration that you can’t get on a normal Strat, which is the neck and bridge pickup together. It’s something you can do on a two-pickup guitar. It has sort of the signature sound of a Fender Jazzmaster or a Jaguar.

What songs or solos can you hear that pickup configuration on?

You know something? That Jazzmaster sound was something I always craved and wanted to use, but I don’t think I’ve ever actually really used it on anything. It was experimenting, trying things out. It did what I wanted it to do: It achieved this different sound and, strangely, in the end I scarcely used it.

What else did you do to the guitar?

At one point I drilled a huge hole out of it and put an XLR socket in it, for some mad reason, which I then got rid of and refilled in again. All these little modifications. I shortened the tremolo arm on it because it suited the way I wanted to be playing a little bit better. I’ve used it as a workbench really for trying out all sorts of different things over the years.

You retired the Black Strat for part of the Eighties and the Nineties when you donated it to the Hard Rock Cafe. Why did you do that?

I bought one or two other guitars from Fender. I went to their warehouse here in England and tried out 20 Stratocasters, and I think I bought four to keep me covered for anything I might need. I think around the time of Live 8 in 2005, I thought I would go back to the Black Strat for a little while, and I got it back from the wall at the Hard Rock Cafe somewhere. I had lent it to them for a long time. I started using it again. I used it on my more recent solo albums.

What attracted you to Stratocasters in the first place?

My boyhood dream was to have a Stratocaster like Hank Marvin in the Shadows had. It was the guitar I always wanted. Lots of other players came along who did nothing but submit to that. Hendrix wasn’t bad on a Strat. It was the guitar of my dreams. When I could afford one, I got one. My first Fender, though, was a Telecaster that my parents bought me for my 21st birthday.

Do you still have that one?

No, I shipped it to America in about 1970, maybe ’68, I can’t quite remember, but TWA shipped it and lost it. I never saw it again. That’s amongst the lost and stolen guitars in my life, of which there are a few. Not too many.

You’re selling your “Number One” Strat, with the 0001 serial number. You bought that one from your guitar tech in the mid-Seventies?

That’s right. He bought it and then I strong-armed him out of it, really. That one’s got to go. It’s a really beautiful instrument. I used it to play the rhythm guitar on “Another Brick in the Wall,” but I don’t think I used it that often. It always felt a little bit more delicate than other guitars, and I didn’t want it to get beaten about with my going on the road, so it’s never been on a tour.

It sounds almost too precious to play.

I don’t think any of them are too precious to play. I play it a lot, and I have it at home most of the time. It’s also on a track called “Mihalis” on my first solo album. There’s sort of a tribute to Hank [Marvin] moment on that track, which I used that guitar for.

You played a ’55 Gibson Les Paul on “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2.” Are you selling that one?

Yes. I bought that in about ’78, because I wanted a nice Les Paul but with P-90 pickups; I like those more than I care for humbuckers. On The Wall, we plugged that through the desk direct — not through an amplifier — so it’s a direct-injected sound straight onto tape during the solo. Then, because we decided it needed a little bit of beefing up, we played it back out through the studio and through an amplifier and remixed it to add a little bit of weight and edge to it.

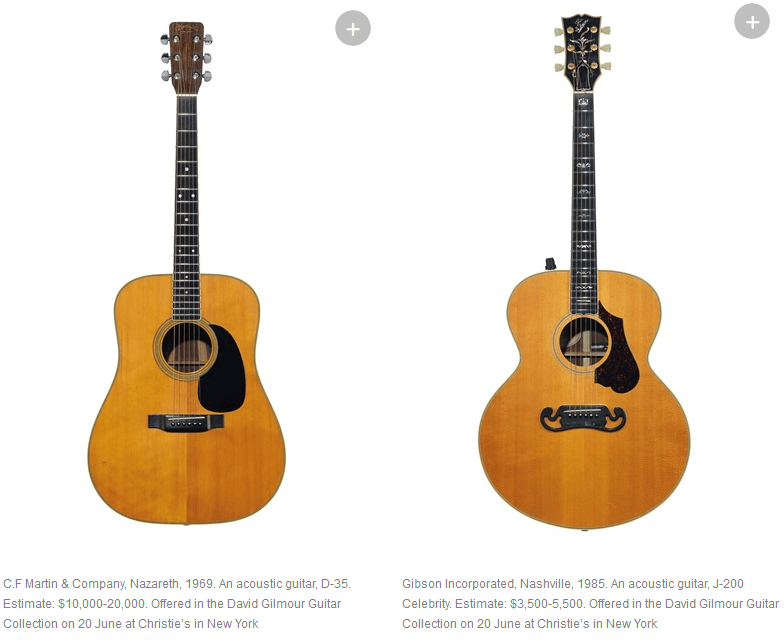

You’re selling the Martin D-35 that you used on Wish You Were Here. I believe that’s one you never wanted to tour with.

Yeah. To take it on the road in the modern age where the drums and bass and everything are hammering away, you’d have a really difficult time amplifying it. You would have to have electronics built into it, and I really didn’t want to mess around with it. It’s such a nice guitar that it really would be bad karma to muck about with it, so you could take it on the road. I didn’t ever want to do that.

When did you get it?

I bought it in New York in ’70 off a guy in the street outside Manny’s in order to do “Grantchester Meadows” at the gigs we were performing that week. I can’t remember why I needed another guitar — I don’t know if one got lost — but we needed it for that, since it’s a quiet, acoustic-type of song with nothing in the way of drums or anything.

You’re also selling the guitar you wrote “Wish You Were Here” on?

I wrote that on a 12-string Martin. I bought it off a friend of mine in about ’72 or ’73, I guess. It’s also in the sale. I wrote “Wish You Were Here” one day in the control room of Number Three Studios at Abbey Road. That riff dragged itself out of that guitar, and it became “Wish You Were Here.” It didn’t go on the road either. By about ’75 or ’76, we got Ovations that had built in electronics that were very good live. They didn’t feed back too badly. One of the Ovations, the one which I restrung to a self-invented high-strung tuning, became the guitar that I wrote “Comfortably Numb” on. That one is also going in the sale. I think it’s been played on pretty much every live version of “Comfortably Numb.”

Are you selling the 1955 Fender Esquire, on the cover of About Face, that you’ve dubbed “The Workmate”?

The Workmate isn’t going. I’m afraid I couldn’t do it.

Is the Workmate your go-to guitar these days?

When I’m in the studio room, the Workmate is the one that I will often pick up or a Black Strat [replica]. I’ve got one or two of my own more recent Fender-issue Black Strats, which are brilliantly good, and I’m happy when they hop into my fingers. Sometimes I can’t even tell whether I’m playing the first original one or these other ones.

But I’m much more commonly on acoustic guitar when I’m in my home. I might have a couple of acoustics sitting around, but the electrics I tend not to play in the house. I’ve got a very nice, nylon-strung guitar that I’m playing quite a bit and my daughter plays. I’ve got a very nice guitar that my wife bought for me that was built by Me&Ro in America [a Me&Ro Ebony Anniversary Guitar]. It’s a very lovely guitar.

Will you be including anything other than guitars in the auction, like your Big Muff foot pedals?

I don’t think there’s a Big Muff in there. But maybe there are a couple of amps.

What does your family think of you purging all these instruments?

I think that they, like me, are very happy that they will do good. The proceeds of this sale will do a lot of good in the world, and we’ll be able to do something positive in this rather negative world we’re living in.

The guitars here will be benefiting your foundation. When and why did you start it?

I think it goes back to the Seventies, maybe the Eighties; it developed out of another one I had before. I’m not sure. I’ve been very lucky in life. I have been very successful artistically and financially. I have felt many, many years ago that I should do something to do a little bit of good with my good fortune. This will be another huge boost to what our capabilities are.

How much money do you hope to raise?

You know something? I haven’t given that a second’s thought. I haven’t got a clue. I’m sure there will be people who look at what is going to be sold, and they will do some guesses on sums. But I’m not going to be that person.

Are you worried people will see you selling all these instruments and think you’re retiring?

I’m neither retiring nor particularly planning things at the moment. I’m sure I’ll get around to something one of these days, but it’s a big commitment.

Have you been writing new music?

I write all the time, which is to say that I come up with a little phrase in my head or on the guitar or piano and jot them onto my phone and log them all up later. And then I think, “I’ll listen to those one day and see if anything appeals to me.” That’s where the process will start next time.

When do you know it’s time to make a new album?

It doesn’t really quite work like that for me. I just start going into my little studio room and playing around with these things. Sometimes I’ll build up a drum track on machines and start turning these little demos into something slightly more substantial, and then they go through two or three levels of building them up until they start sounding like a song. When I have enough things that have started sounding like songs, I’ll make a decision about when or how to make an album. It’s like pushing a snowball down a hill: It gradually gathers momentum.

What kind of music has been coming to you lately?

It’s very hard to talk about the writing process and how I record and use little snippets. Sometimes I’m hearing a piece of music as it’s playing on the radio or on television, and I record 10 seconds of it, just for a little particular thing and rhythm or something attracts me. I will go back to that little moment to say, “What was it about this that attracted me and what can I … not steal, but pay homage to or extract a feeling from it.” Most of [the ideas] are things strummed on acoustic guitar or plunked on a piano. Ninety percent of them, I will not understand why on earth I jotted them down and recorded them, but I have several hundred of them. I’ll find something good in there.

It sounds like you’re too curious about music to retire.

Retiring is not a hard and fast thing for me in my life. I don’t really have to retire. I don’t have to say those words. I don’t have to state that have retired or anything like that. If I retire, it will be a quiet, unnoticeable process at some point. But I’m not at that moment.

Do you look at this auction at all as closing a chapter on Pink Floyd or the past?

I don’t. I don’t think I do that. I will obviously be sad to be losing some of these instruments, but I will also be slightly relieved at losing the weight of having all these instruments and not knowing what is going to happen to them or where they’re going to go. I want them to move on. I’ve been their custodian for a number of years and now it’s someone else’s turn to have them and use them, to create with them.

Christie’s to auction more than 120 guitars from the personal collection of the Pink Floyd singer and songwriter, including the iconic Fender Stratocaster played on The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals and The Wall

Christie’s to auction more than 120 guitars from the personal collection of the Pink Floyd singer and songwriter, including the iconic Fender Stratocaster played on The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals and The Wall