With thanks to Sound & Vision Magazine

© 2003 Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S., Inc.

Tales from the Dark Side

James Guthrie talks about his great gig in the studio remixing Pink Floyd’s classic in surround. By Ken Richardson Photos by Ebet Roberts

James Guthrie talks about his great gig in the studio remixing Pink Floyd’s classic in surround. By Ken Richardson Photos by Ebet Roberts

The scene: the London Planetarium. A fitting venue to visit The Dark Side of the Moon. But it’s 1973, and this is the album’s maiden voyage. And a quadraphonic mix, not approved by Pink Floyd, is being played on terrible, destined-to-be-forgotten speakers. The band members decline to attend and are represented by cardboard cutouts.

The scene: New York’s Hayden Planetarium. Another fitting venue to go to the Moon. But now it’s 2003, and this is the album’s 30th-anniversary relaunch. And a six-channel mix for Super Audio CD, approved by the band, is being played on impressive ATC speakers. The band members still aren’t here (their schedules won’t allow it), but they’re represented by their longtime engineer, James Guthrie, who mixed the album for surround sound. And while he certainly isn’t made of cardboard, he admits he’s a little stiff—and nervous.

That’s because Guthrie’s usual haunts aren’t planetariums but, as he calls them, “dungeons,” the small, dark studios where albums are recorded, mixed, and mastered—and where, occasionally, masterpieces like Dark Side are created.Guthrie wasn’t at Abbey Road Studios for that album’s creation, but he has been associated with Pink Floyd for nearly 25 years, since he co-produced and engineered the band’s 1979 release, The Wall. So they chose him to remix Dark Side for Capitol’s SACD. Which, at first, made him nervous.

After all, this wasn’t just any old lunar expedition. The Dark Side of the Moon stayed on Billboard’s Top Pop Albums chart for a record 741 weeks—more than 14 years. All told, in all formats, it has sold more than 30 million copies worldwide. And the album itself? It started off as just another LP for guitarist David Gilmour, bassist Roger Waters, keyboardist Richard (Rick) Wright, and drummer Nick Mason. But it ended up making history as both a record and a recording. With its kaleidoscopic music and laser-sharp lyrics, the album told a vivid tale of modern pressures and age-old insanity. And it was an amazing sonic adventure. As Wright has said, “It seemed like everyone was waiting for someone to make this album. It touched a nerve.”

No wonder Guthrie was nervous. Yes, he had done surround mixes of Pink Floyd: The Wall for DVD-Video and Waters’s In the Flesh for SACD. But this was different.

“There were certainly some sleepless nights before I started,” Guthrie says. “I vacillated wildly between how conservative I should be and how far I should go. In the end, I thought to myself: ‘This is silly. I’m just going to forget about all of that stuff and concentrate on the music.’ Because there’s only one important thing here: Is it emotionally satisfying?”

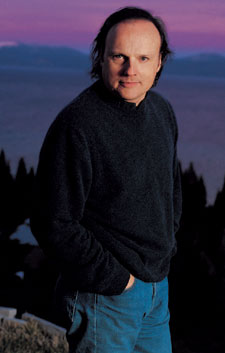

Guthrie and Louis stretch out in his studio, Das Boot.

I’m talking with Guthrie in his home studio, Das Boot, named by a visiting band in recognition of Guthrie’s “fixation” on submarines—specifically, American diesel boats of World War II. And indeed, his studio is adorned with gauges that summon up small, dark spaces of the past. Yet the London-born Guthrie has finally escaped the studio dungeons of his own past. His “Boot” is a spacious, comfortable room, with three long windows affording a spectacular view of the Sierra Nevada Mountains that surround his Northern California home.

This is where Guthrie and his assistant engineer, Joel Plante, started work on Dark Side last November—when the original 16-track master tapes arrived from Abbey Road Studios. “The tapes were in quite good condition,” Guthrie says, “but they weren’t well marked or logged. At first, we only had handwritten track sheets and a few scribbled notes. But then the terrific librarian at Abbey Road, Ian Pickavance, sent over copies of the daily job sheets. So we were able to do a great deal of sleuthing work.

“We were always trying to find little bits of music to make sure we had everything. As far as I was concerned, it was not acceptable to miss even one element. And I hope we haven’t.”

By the middle of January, Guthrie was ready to play his initial six-channel mix for each member of Pink Floyd. “I didn’t know what to expect. They’re a fairly low-key band—just in terms of their characters. They don’t get excited easily. But they were very enthusiastic about this SACD. I haven’t seen Rick and Nick like this for years. The band asked for some changes, but thankfully, none of them were major. And there was very little in terms of the placement of instruments. It’s crucial for fans to understand that this mix has the band’s input and endorsement.”

He acknowledges that some fans are wondering why the album’s original engineer, Alan Parsons, wasn’t involved with the remix. It was Parsons who did the quad mix in 1973.

“The band listened to that quad mix and elected not to use it,” Guthrie says. “I used the original stereo mix as my guide, because it captured the detail and emotion of the songs.

“The focal point of the six-channel mix is the listening position, not any of the speakers. What I have tried to do for many, many years is to make the speakers disappear—so that you’re aware of sound being everywhere. You get immersed in the sound and can experience the music.

“When you first listen to the mix, it’s very easy to think that everything is everywhere. But in fact, there are things moving around, there are elements in the back. But it’s all for a reason, and it’s relevant to the music. In the end, I wanted to keep the album’s homogeneous sound but also try to spread it out. It was a combination of keeping the heart and soul of the original but also making use of the larger soundstage.”

Author Ken Richardson and Guthrie

The heart and soul of my time with Guthrie is spent sitting and listening to his mix. The main speakers are ATC’s SCM-150ASLs, the domestic version of the speakers used at the Hayden Planetarium. As Guthrie’s two cats, Louis and Manu, glide in and out of the room, we go through the entire album, track by track. And Guthrie is eager to provide a remixer’s commentary.

Speak to Me. “It’s basically made up of speaking voices. When the band finished listening to the initial mix, I was surprised that their first comments related to the album’s various speaking voices. And then I realized I had awoken a 30-year-old argument. In 1973, Roger and David had disagreed about those voices. Roger wanted them to be drier and more intelligible. David wanted them to be wetter and more mysterious. In the end, we compromised—the same way they did in 1973.”

Breathe. “There are so few elements here—drums, bass, guitar—until later when the Hammond organ comes in. There would be a problem if you started to separate things too much. So this was a case of trying to keep the sound anchored while spreading it.

“Going back to the very first generation of tapes, everyone assumes that the drums will benefit—which of course they do, because you have more transients. But everything benefits; everything is richer and has more depth.

“In the meantime, something had always bothered me about this track. . . . For years, I had been thinking to myself, ‘There’s some ultra-low-frequency rumbling going on. What the hell is that?’ I checked the multitracks, and—there it was, coming from that lap steel guitar. It wasn’t coming from the guitar itself or David’s amp. It was being picked up in the studio somehow. And we were able to get it out.”

On the Run. “The opening organ swirl through the Leslie speaker is actually circling around you, but it’s just for a short period of time, and then the sound fades out—so you don’t really get a chance to become seasick. The synthesizer sequence running all the way through is coming from everywhere, but it’s predominantly in front of you, so you get the feeling that it’s a bit more in your lap.

“David wanted the mix to more closely resemble the ‘general muddiness,’ as he put it, of the original. So I did that adjustment.

“This is the only song where I actually added something. The multitrack tapes had some extra guitar that wasn’t used in the final stereo mix: a bit of backward guitar and then a dive. I liked it and put it in [starting at 1:15 into the song]. The band agreed.”

Time. “It was a very difficult song to mix in terms of making it groove correctly, with all those different instruments—the jagged guitar, the piano, the organ. It was tricky to find that balance. But when I did, I felt that it was swinging more than the original stereo mix.

“Placing the rototoms was a case of trial and error. I just tried to settle on a spot where they were making use of the space without being too distracting.

“By the way, the length of time from when the clocks finish chiming to the first downbeat is longer on the original multitrack tape. For the stereo mix, they shortened it. And we’ve shortened it to match.”

The Great Gig in the Sky. “In the first part of Clare Torry’s vocals, I had originally made her more intelligible, a little drier,more focused at the front—just louder. But Rick thought the overall impact was stronger when she was a bit wetter and more receded in the mix. So I checked the original stereo, and I was surprised to find that she’s buried in there. . . . Your memory of these things changes. It’s the way that we perceive music: our minds tend to fill in the blanks. She’s actually still louder now. But Rick wanted to recapture the emotion of the original. And it’s his song.”

Money. “The opening sound effects work really well in the original stereo mix. At one point, the panning surprises you. The sounds start moving, and you think there’s one that’s going to move over here—and it doesn’t. The stereo pulls you back to the same speaker. And even though it’s just two channels, it creates a specific effect. So I spent quite a long time on the surround mix, trying loads of different patterns. This one at least does what the original stereo did. You get an X for a second, but then it pulls you back to the same speaker, and you’re not expecting it.

“Overall, the song is punchier now, it drives harder. In the sax solo, Nick goes to the ride cymbal. In the stereo mix, you can hardly hear that. But going back to the first generation of tapes, you can hear he’s doing this great sort of jazz groove.

“In David’s middle solo, when he drops down completely dry, I wanted you to feel like you could just reach out and touch the guitar. It’s right there.”

Us and Them. “The band liked the initial surround mix, so it’s basically the same now. Rick, who wrote the music for the song, was delighted. He said he was never happy with the stereo mix.

“The sax plays a very different role here than in ‘Money.’ It has a close, breathy feel to it—but it also works well when it’s wet. So for the surround mix, it’s mostly in the center channel—and there’s reverb going on in the back. But by also feeding it to the left and right front with less echo, you retain the closeness and the breathiness. I know it sounds incongruous, but it’s a great way of achieving something that is present and in your face while, at the same time, having it roomy and lush.

“In the choruses, there’s a lot going on. There’s stuff playing in the same register, there’s intermodulation distortion on the girls’ voices on the multitracks, and the sax is now wailing. So I tried to achieve some distinction for the voices, but I needed the slightly messy approach, too—as well as the big dynamic lift. Hopefully, you retain the detail, but you still get the size.”

Any Colour You Like. “Originally, I had gone a bit further in the mix, and Roger asked me to tone it down. The ping-pong guitars are now a little less dramatic. David wanted it that way as well.”

Brain Damage. “I made Roger’s voice louder, which he really liked. I think it’s a lot more intelligible. David thought it was a bit too loud. [laughs]

“The background vocals aren’t just in the back. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be part of the same performance. And that would be a real problem in the car, with all the extremely high ambient noise. It would be a case of the people sitting in the front seats saying, ‘We’ve got rhythm section up here! How are the vocals back there?’ ‘Not bad. How’s the groove up there?’

Eclipse. “I prefer this vocal balance to the original. I think the build is somehow better, and you can hear more of the subtleties in the harmonies at the end.”

Author Ken Richardson and Guthrie, joined by assistant engineer Joel Plante.

What’s next for Guthrie? First, he has to finish mixing the band’s concert film Pulse for DVD-Video. Then, he hopes to start his own boutique label. And then . . . more Floyd? “Nothing’s been decided, other than we’ve talked about doing more surround stuff, but only touched on it. I think it will hinge on how well received Dark Side is.

“I personally would love to do Meddle. It’s one of the better-sounding Pink Floyd albums. I’d also like to do Animals, which is probably one of the worst-sounding Pink Floyd albums. I love it musically, but the drums sound like hatboxes. Wouldn’t it be great to take Animals, put it in the correct spatial environment, and work on the individual sounds? And of course, I’d like to do The Wall, having done it originally.”

Does Guthrie have a multichannel wish list of other artists? “You know what I would jump on immediately? I would love to do a surround sound mix of Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love. Kate is a dear friend of mine, and I’ve spoken to her about it—but Idon’t think she’s ready to let go of it yet.”

It’s a long way from London to California, a long way from the stereo of the ’70s to the six-channel sound of the ’00s. But in some ways, the more things change, the more we need them to stay the same.

“Whenever I had any extra money as a kid,” Guthrie remembers, “I would buy a stack of vinyl. And I would sit down between my two speakers, and I’d be transfixed. I would listen for hours and hours and hours without moving. I’d be thinking, ‘How did they do that?’ People don’t listen like that anymore. They don’t have the time, they don’t have the focus. If The Dark Side of the Moon in surround helps rekindle our interest in just sitting and listening and experiencing music again, what a great thingthat would be.”

Another Phase of the Moon

Original engineer Alan Parsons explains why the SACD mix doesn’t speak to him. By Ken Richardson

Original engineer Alan Parsons explains why the SACD mix doesn’t speak to him. By Ken Richardson

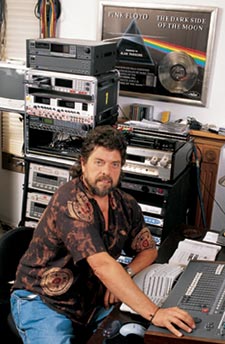

Photos by Ebet Roberts

Walk into the home of Alan Parsons, nestled in the hills of Santa Barbara, and you’ll see ample evidence of his illustrious career. There are so many gold and platinum records on the wall of the studio annex that they spill from the hallway and fill the kitchen. There’s everything from Red Rose Speedway, which he helped record for Paul McCartney, to Eye in the Sky, one of the many albums by his own Alan Parsons Project. Then there’s the original gold record for Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which Parsons engineered at Abbey Road Studios.

But open up the Super Audio CD of Dark Side, and you’ll see no evidence that Parsons had a hand in the six-channel mix. That’s because he didn’t.

“Of course, I understand Pink Floyd would want to take on their engineer of the past 25 years for this project,” Parsons acknowledges, referring to James Guthrie, who was tapped to do the surround mix. “But I think it would have been nice if I had received a call just to say, ‘Would you like to be involved?’ I had been consulted when Dark Side was remastered in 1992.”

Some fans contend that the stunning sonic architecture of the original album is at least partly due to the engineering expertise of Parsons. Then again, since its 1973 release, some band members have occasionally tried to downplay his role. There’s plenty of room for differing memories and opinions in the span of 30 years. David Gilmour and Roger Waters themselves often disagree on their own roles in Dark Side.

“It’s a function of human nature,” Parsons observes, “that everybody who contributes to a project feels that their input is the make-or-break, crucial thing—the thing that took it from good to great. I don’t think I’m trying to say that, but I would say that without me, the album might have been different.”

In the early 1970s, Parsons engineered Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother before doing Dark Side, and he then made quad mixes of both—commissioned by EMI but not okayed by the band.

“I’m not surprised that Pink Floyd rejected my quad mix of Dark Side for the SACD,” Parsons says. “I did the mix very quickly. If I’d known that the record would sell in its millions, then I would’ve insisted on having more time. There’s stuff missing from the quad mix. I just didn’t have enough tape machines in the studio to get it all in. The quad was a compromise; I have no problem admitting that fact. I did it single-handedly without automation. But the feel of that mix is pretty exciting. Conceptually, it wasn’t so wrong that I shouldn’t have had a crack at the surround mix.”

Parsons gave a detailed account of the making of the quad mix in “Four Sides of the Moon,” a paper he wrote in 1975, originally published in Studio Sound magazine. And last December, at the Surround 2002 Conference, he discussed his philosophy of surround:

“The surround experience shouldn’t be a stereo experience with ambience. It should be four stereo sound fields. I tend to work on the outsides when I mix for surround. A lot of people choose to go into the room, but that’s asking for clarity problems—it clouds things up. In my quad mix of Dark Side, I liked the idea of action happening in all four channels. I wasn’t particularly interested in it sounding like a band onstage.”

Today, Parsons tells me his impression of Guthrie’s six-channel mix. “I’m generally rather disappointed. It’s not very discrete. There is some discrete information in there. But I found myself, about two-thirds of the way through, kind of forgetting that this was surround. James was possibly a little too true to the original mix. He could have taken some risks, as I did on the quad. One of the parameters I always work with when I’m mixing for surround is: Keep the Interest. If there’s nothing going on, then stick something in the back.”

That said, Parsons agrees with Guthrie’s subtle use of the center channel. “He’s right with me on that. If it was a perfect world, I’d be fine with the center channel. But since the center can be set up in someone’s home at anything but the exact correct level, I’m not really interested in it. Also, artists don’t like to have their voices isolated in the center for microanalysis—or for possible karaoke versions.

“Overall, I think that James has done a great job in cleaning everything up. And his surround mix has some very good moments. But it also has some rather dull moments.”

Author Ken Richardson (left) listens raptly as Alan Parsons describes how he’d have shaped the sound field in The Dark Side of the Moon’s multichannel remix.

Even though Parsons and his fiancée, Lisa Marie Griffiths, are to be married in only ten days, he takes the time to conduct a moment-by-moment listening session. He goes beyond A/B comparisons to A/B/C comparisons: the original stereo mix, his quad mix, and Guthrie’s six-channel mix. Parsons and I are in his studio, surrounded by B&W Nautilus 802 speakers. And since Track 1 of Dark Side was named after the line that he would say when testing a microphone, I just couldn’t resist following suit: “Alan Parsons: speak to me.” His reply: “Any colour you like!”

Speak to Me. “In the stereo mix, I put the heartbeat coming slightly from the right, because if a person is facing you, the heart is on the right. James has the heart dead-center.”

Breathe. “I like James’s placement in the beginning more than my quad mix. It works really well. But I find the vocal sound to be harsh.”

On the Run. “In the stereo mix, at the beginning, I took the organ swirl and opened up the panning gradually, wider and wider. In the quad, the swirl goes right ’round the room. In James’s mix, it doesn’t open up at all.

“After hearing his mix for a while, I think I’m hearing stereo with a bit of surround.”

Time. “In James’s mix, the rototoms are underfeatured, too mixed in, not jumping out at you enough. He’s made more of a feature of the big bass notes.

“In the main section, James’s mix is nice and balanced, but the placement is only a little better than stereo. Still, he has improved the drum sound here, no question.”

The Great Gig in the Sky. “I tip my hat to James for sorting out the correct bits of Clare’s vocals. And he has improved on the stereo mix, which is a bit wishy-washy. The stereo is heavy on the Hammond organ, and Clare’s a little too far down. In my quad mix, the Hammond is barely there, which shows you I really wasn’t being faithful to the stereo mix. The quad sounds pretty good, but James still has the edge. His mix is definitely cleaner, and he’s brought Clare out a bit more.”

Money. “I mostly like James’s placements in the surround mix. But what he’s done with the sound-effects loop is very illogical. You have to wait a long time for something to appear in the left front channel. In the quad, the pattern goes around the room in a circle, starting again in the left front each seven beats. If I’d done the surround mix, I would’ve made the loop continue around the room the whole time, so that the circle itself would actually rotate.

“Listen closely when the loop re-enters later in the song. In both the stereo mix and the quad, the timing wasn’t exactly in sync with the music. James has corrected that for his mix. It was something I was dying to do for 30 years.

“I went crazy with the third guitar solo in my quad mix. Thirty years later, I wish I hadn’t. It’s going all around the room. Very 1970s—just like the early days of stereo.”

Us and Them. “I think it was the right choice in my quad mix to make the vocal echo go around the room in a circle. James has a better balance, but I’m disappointed with his vocal echo placement.

“For the album, I pretty much decided when the echoes should be there and when they should not be there. . . . They’re on the word ‘with,’ but they’re not on ‘without.’ And when it comes to ‘what the fighting’s all about,’ I just echoed ‘bout, bout, bout, bout’—because ‘bout’ means ‘fight.’ But James missed that: he’s got ‘about, about, about, about.’

“For the album, I pretty much decided when the echoes should be there and when they should not be there. . . . They’re on the word ‘with,’ but they’re not on ‘without.’ And when it comes to ‘what the fighting’s all about,’ I just echoed ‘bout, bout, bout, bout’—because ‘bout’ means ‘fight.’ But James missed that: he’s got ‘about, about, about, about.’

“James’s choruses are just a touch on the cluttered side. Everything is on the same level. In the stereo, they hit you harder [Parsons thrusts his fists out in front of him]: ‘Forward, he cried!’ ”

Any Colour You Like. “On the downbeat every four bars [starting at 1:46], there’s a bass-synth note that’s totally missing from James’s mix.”

Brain Damage. “In the quad mix, the guitar picking is in the rear. This is definitely surround. And you can hear every note the girls sing. Even in the stereo mix, you don’t get that. James is basically stereo with the voices forward.”

Eclipse. “In James’s mix, the closing heartbeat actually sounds like what it is: a kick drum. It’s clean as a whistle, but I think there was a certain amount of mystique about it before.”

If there’s any mystery about what Parsons can achieve in a contemporary multichannel mix, it’s dispelled by what he calls “my first modern-age attempt at surround”: On Air, his 1996 album as remixed for an acclaimed DTS 5.1 CD. Eventually, he hopes to license the surround rights to the rest of his back catalog from Arista.

Meanwhile, after his wedding and honeymoon, he plans to finish work on a new album, scheduled to be released in January on DVD-Audio by the Myutopia label of the 5.1 Entertainment Group. Assisted by his 26-year-old son, Jeremy, Parsons has fully embraced electronica. “The album is essentially a more computerized slant on what I’ve done in the past, with less vocals. I’m making no pretense: I’m trying to capture a younger, more clubby audience.”

It’s no wonder that Parsons, having gone to the Moon and back, still keeps his eyes on the sky and his ears on the cutting edge. After all, this is the man who, way back in 1975, predicted the future when he saw the Ken Russell film of Tommy and wrote about its use of “a quintophonic system—doubtless an indication of things to come.” Forward, he cried!

All That You Hear By Ken Richardson

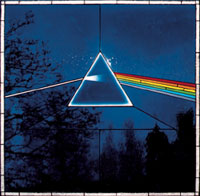

PINK FLOYD The Dark Side of the Moon Capitol

Music * * * * *

SACD * * * *

Look at the redesigned cover: the original art is now enshrined in a stained-glass window. It’s a beautiful transformation—as well as a perfect metaphor for the six-channel mix inside. For some listeners, this may mean that the mix is overly respectful. For others, it may mean the mix is appropriately reverent while still providing a robust surround experience.

For me . . . James Guthrie has done a marvelous job of taking the church of The Dark Side of the Moon and transforming it into a cathedral. He begins with some surround-by-stealth in “Speak to Me” and “Breathe” before pulling you into the drifting (but not dizzying) movements of “On the Run.” He envelops you in the big choruses of “Us and Them” and “Brain Damage” but still shows you newly identifiable layers of sound. And then there are the exquisite details: the scraping guitar in the middle solo of “Money,” the tactile clocks of “Time.”

For me . . . James Guthrie has done a marvelous job of taking the church of The Dark Side of the Moon and transforming it into a cathedral. He begins with some surround-by-stealth in “Speak to Me” and “Breathe” before pulling you into the drifting (but not dizzying) movements of “On the Run.” He envelops you in the big choruses of “Us and Them” and “Brain Damage” but still shows you newly identifiable layers of sound. And then there are the exquisite details: the scraping guitar in the middle solo of “Money,” the tactile clocks of “Time.”

That said, the SACD falls short of five stars for two reasons. First, no matter how faithful the mix is or isn’t, I still think the use of the center channel is too subtle. The one time it’s used prominently, for the breathy sax of “Us and Them,” gives me a chill that I wish I could get again and again. Second, though the new cover is splendid, the 18-page booklet is disappointing. Yes, the lyrics are here, but there are no new essays or liner notes. Instead, you mostly get images of Dark Side paraphernalia. Do we really need a 1-inch-square photo of a Pink Floyd “Millennium Series T-shirt, 1999”?

If you don’t own an SACD player, this hybrid disc will let you hear the stereo mix on your CD player. My advice: buy an SACD player! Think of the surround mix any way you like. This reissue still eclipses every Moon that came before.