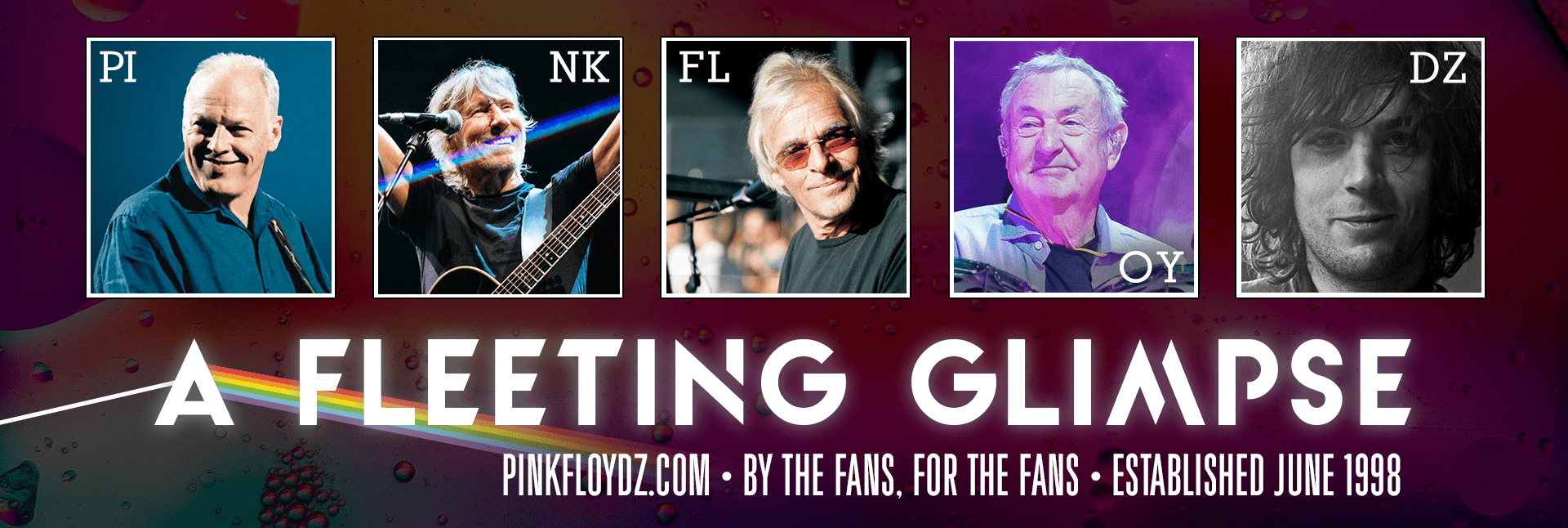

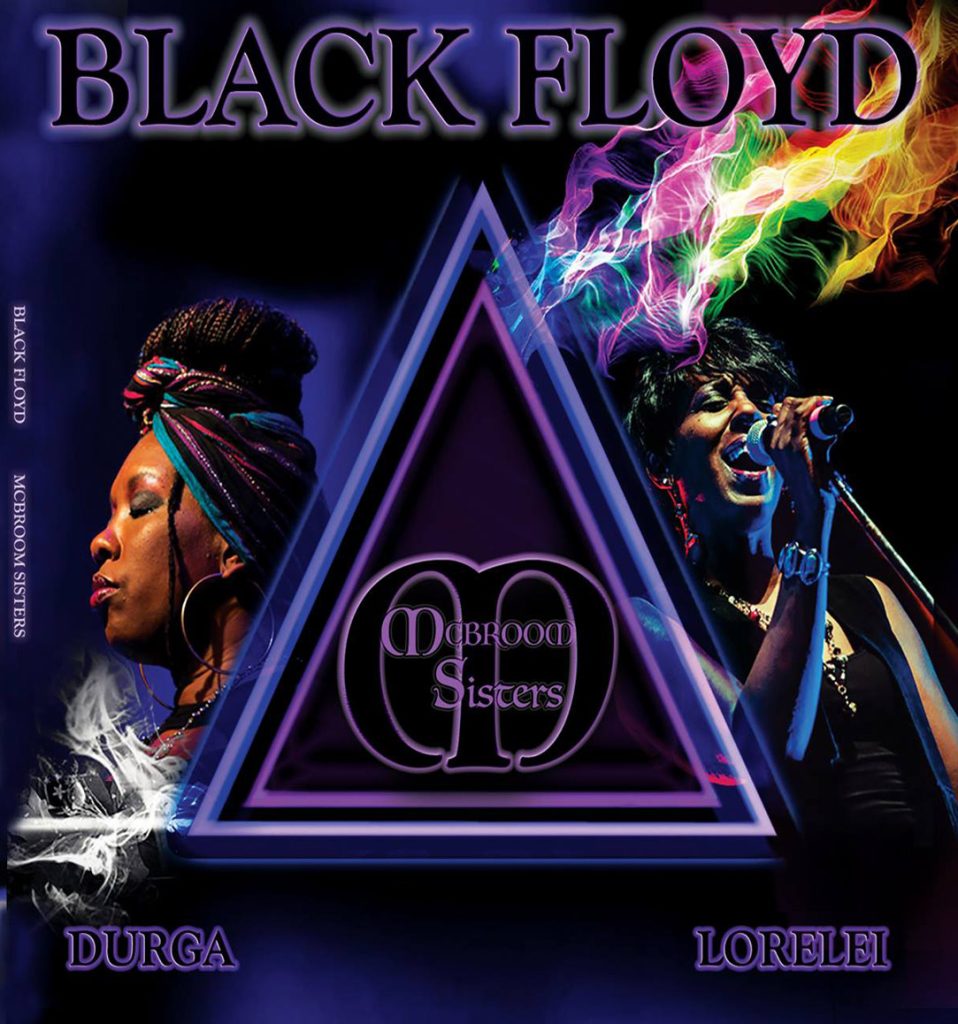

The McBroom Sisters: A Retrospective on ‘Black Floyd’ featuring Lorelei McBroom, Durga McBroom, and David Domminney Fowler

Released amid the 2020 COVID pandemic, Black Floyd presented a fresh take on the tribute album, featuring stunning Pink Floyd covers led by the powerful vocals of Durga and Lorelei McBroom, who were once backing vocalists for the band. This album not only showcases their impressive renditions but also includes original songs that reflect their musical roots, creating a cohesive journey through Rock and Roll.

The McBroom Sisters lend their voices to both lead and backing vocals on this album, blending classic Pink Floyd covers with original compositions co-written alongside prominent musicians such as Guy Pratt and Lemmy Kilmister, plus others! This album showcases an impressive array of talent, featuring David Domminney Fowler from The Australian Pink Floyd Show as both producer and guitarist, alongside special guest vocalists Louise Goffin, Lara Smiles, and Emily Lynn. The guitar work includes contributions from Fowler, Fernando Perdomo, Randy McStine, Billy Sherwood, and Steve McElroy, while the keyboards are played by Dave Kerzner, Jon Carin, Jason Sawford, Dave Innis, Fowler, and Paul Grant. The bass lines are delivered by Fernando Perdomo and Ricky Howard, with drums provided by Derek Cintron, Paul Bonney, Nick Mason, and Fowler. Additionally, the album features trumpet by Paul Litteral, saxophone by Mike Kidson, and violin by Lili Haydn.

We had the opportunity to speak with Lorelei, Durga, and David, who kindly took the time to provide their perspectives on this unique project and its development. Join us as we explore an album that stands out brilliantly and could easily be regarded as a modern Pink Floyd classic.

AFG: Black Floyd offers a diverse mix of original tracks and reinterpretations of Pink Floyd songs. What inspired the selection of these specific Floyd tunes to complement the original music? Despite their stylistic differences, they seamlessly come together to create a cohesive musical experience honoring the roots of Black Culture and Rock N Roll.

LM: Well, there were bands that had Durga and I go on tour with them and they allowed us to do lead vocals, so through trying this and trying that we found songs that we were really good at. I loved Have A Cigar for example, but I felt like the groove could be just a little bit tighter and a little bit funkier. It was like going back to the Blues roots and that’s how it was played. I think Poles Apart, for example, is just a beautiful song and it’s also reminiscent of my folk roots. The melody, the guitar parts, so that’s kind of just mesmerizing to me. Neither one of us grew up singing in church.

We both grew up singing either folk music for me, pop music, and we got into rock n roll really early. It was just kind of an extension of our natural vocal style. Gilmour has such a a beautiful voice, so to have a female doing those melodies just works. Yet, like with Have A Cigar I could give it my ‘rock n roll kick you in the ass’ style because that’s another part of me, pretty much because of singing blues. I got really into this whole other mindset and that came out of working with The Stones. Because they were into old blues, backstage was all old blues I had never heard of, and it was a very interesting learning experience for my growth.

DM: We picked PF songs we’ve always loved to perform. When you sing on these songs year after year, you often think of how you’d like to sing the lead. So we did! We wanted to choose a selection from several Floyd eras.

AFG: What inspired the creation of the album?

LM: Back in 2013, is when we first started recording with a guy named Dave Kerzner. Dave is a solo artist that ended up doing some things with Durga and me on his albums. He had done a recording of The Great Gig In The Sky working with Alan Parsons and that’s what started it. He had Durga and I sing on this, and he was like “Hey, do you want to do some more covers?” So, we did and every year we ended up doing Cruise To The Edge, which is this Yes hosted cruise and after the cruise we would go in the studio at Dave’s place in Miami and record a little bit more, it was like every year we would do a little bit but we never actually finished.

Until the pandemic, we were finally shut in. And I played the stuff for Dave (Fowler) and he and I were like you need to do the production and finish it, because Dave has such a wonderful ear and he’s got the skill, and we had the time. That was the main thing was having the time, because all of us were in different cities doing a tour, I’m over here, Durga’s over there – now we could pull it all together.

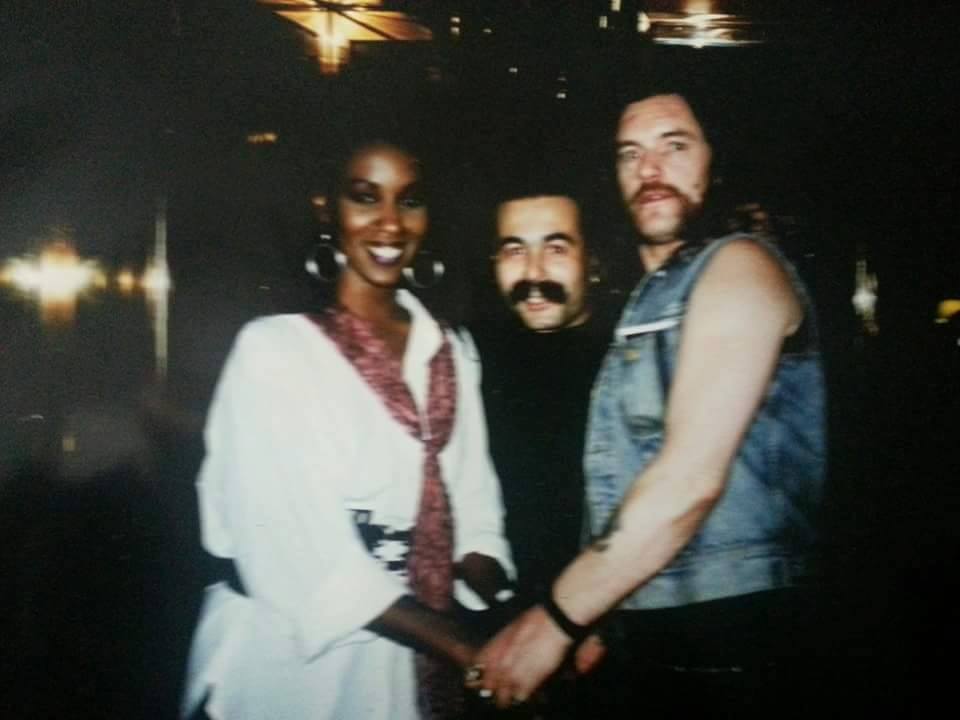

The McBroom Sisters with Dave Kerzner and band

DDF: It was kind of a mish-mash of stuff where they recorded bits over a long period of time. It kind of wasn’t an album and then before COVID kicked in, Lorelei initially had a deadline of having it done by February of 2020 because she was going to go do Cruise To The Edge. We were on tour for the first few dates before the whole thing got pulled in 2020, and she was playing me stuff, and it was…I am going to be diplomatic here but it was clear to me that it was being rushed just to kind of meet this artificial deadline and we were hearing the same four songs round and round with minor improvements. It’s like well that’s great but what about all these other songs? And I personally, when I had listened through to them, I said “this isn’t good enough,” and I wasn’t involved in the project at all apart from one song which we had done. I had worked on one of Lorelei’s songs that I have done completely independent from all the other recording.

I just as a friend was going, “the content is there, the track is there, and the people are playing fine, but the mix isn’t right, there is too much here…need to add more this/that, etc..” She had said: “We haven’t got time for that, it’s coming out in two weeks!” and of course with COVID, suddenly that ‘its coming out in two weeks’ wasn’t happening, which was great. We were sitting at my place and I remember Dave (Kerzner) sending across his mix of Poles Apart which was the first one of the eleven I hadn’t had anything to do with and we just listened through to them at my place through my studio monitors where I got my set-up and frankly, I wasn’t impressed with it. I thought it sounded bad and she agreed.

AFG: Sonically?

DDF: Sonically, it just sounded bad. The thing that Dave Kerzner had done well was he got the people together and things were mic’ed nicely and the performances were there.

AFG: So you had had the multitracks to work with?

DDF: I didn’t at that time, but the mixing of it was just abysmal. Nothing was in a space, it all just sounded like someone had gone like that [gestures closing of hands] rather than there and there [spaces hands out]. I just think it was a little bit rushed at the end and I think he was dealing with his own album as well and trying to get everything out on time.

LM: I was also under the impression that the engineer he was working with was not really a top shelf engineer, and that added to the limitations. We were limited by whatever this guy was capable of doing, because Dave (Kerzner) is not an engineer.

DDF: What ended up happening is we ended up saying “Can you send me the multitrack? I would like to try a mix on this one song,” and we got Poles Apart out of that. That to me is an odd memory, because it was the start of the pandemic and we were in our first lockdown, and it was totally quiet outside, and I’ve got what we call a high street, I don’t know what you call that equivalent in America but it’s the main shopping street in my area and I live on a little road off that and usually you can hear all the noise and there was nothing. It was totally quiet, spookily quiet. We were mixing this… “Did you know.. did you know” from Poles Apart, and I was hearing all these sounds and its so quiet and eery outside. You know when an eclipse happens? It’s dark in the middle of the day, and it’s like… This is weird, it was like THAT, but for months wasn’t it?

LM: Yeah.

DDF: I added some extra guitars to it because in production there’s a ‘Rule of Two…’ If you want to step to something, you don’t just want to have one thing come in, you have two things come in. Then you remove two things and I said “Well that steps up to there but we want to have another guitar in there,” so I started adding bits and it sounded wonderful and we sent it to Durga. The end mix of it was like: [deep exhale] “That’s beautiful, right now everything else has to be this good!” Initially the deal was, because Lorelei was living with me at my house for that first six months of the pandemic, to send over the songs that are sort of mostly Lorelei’s, and I’ll work on those and Dave (Kerzner) can work on the Durga songs because she’s in America and I thought that would be nice, he can do half of it and I can do half of it and it was all good. He started sending over tracks and we worked on Have A Cigar and On The Turning Away.

I would get them and we’d mix them, and at first all the tracks were there so I was just mixing and maybe adding in a rhythm track or if I wanted a synth in there, to lift it or do whatever. Then as it went on, five tracks in I would say “Can you get me that one? Etc…” and it would come through and it would be an acoustic guitar, a click track and a couple of vocals and that’s it. I was asking, “where are all the other instruments?” – “Oh! They haven’t been done…” Which explains why, in February (2020) and we were saying where’s the album? Because there was nothing played on all those other songs! It was like a rough-ish vocal, a click track and an acoustic guitar. It just hadn’t been finished.

That’s really where it kicked into overdrive. I was like… “Right, I’ve got to play guitar! I’ve got to play keyboards, etc.” and I am certainly not a brilliant musician at every instrument, but I can play them in the studio. I can play keyboards with one hand whilst doing something else. It was really when we got to Wish You Were Here where it literally was just Dave (Kerzner) on piano for tuning and there was one acoustic guitar that was just completely out of tune and out of time that I just ditched, a click track, and then there was Lorelei, Durga and Louise (Goffin) singing.

AFG: How were you able to capture the essence of the original Floyd classic while still giving a fresh take on ‘Wish You Were Here’? The rendition starts off just like the original, but then develops its own unique presence. It’s truly beautiful.

LM: Thank you, we’re really proud of it.

DDF: I was just listening to it one night and we were having that sort of dystopian nightmare of the lockdown and the pandemic, I was sitting there, and I thought I want to go really weird and odd on this. I want to make it sound NOT like the nice acoustic. I wanted it to sound dark and like it’s just representing this moment in time. The only thing that stayed was their vocals, and I got some of the top end of Dave’s keyboard and put a delay on it to kind of make it trippy. We started sounding like the Floyd version, but then I thought let’s just get the dirtiest sort of drum loop and just distort it.

I’ll be honest with you, I was really scared to play it for them at first. I was listening to this thinking they are either going to love it and go: “Wow, it’s something new!” or they’re going to go: “What the fuck have you done to this song!?” [laughs] Its the dynamic change, I say if you’re going to do something that’s different, be bold with it. Don’t go half way. We just had to go full on, and I also thought it really suited the way Louise’ (Goffin) vocals were, she hasn’t got the same style of voice as Durga and Lorelei. I could treat her voice with a more electronic sort of style.

DM: It was my idea to ask Louise Goffin to sing with us. We all grew up together and went to school together as kids, and as I’m sure you know she is part of the Floyd family in that David Gilmour produced her first album. Louise is so incredibly talented. I was really happy to have her as a part of this project.

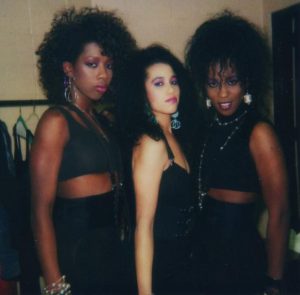

Louise Goffin with Lorelei and Durga

DDF: Again, usually where you would have the acoustic solos playing and all of that, I actually picked up my old Gibson ES-330, ran it through a UniVibe and “Bluesed” it up. It was like everything that is the opposite. If there was an acoustic, I’m gonna do it on an electric. If there were nice sounding drums, I’m going to distort them. It was like turning the whole song upside down to produce something that was equally as beautiful but without it being the same. That, to me was a real high point to the album.

LM: Definitely! I also made a video that was on a whole other mission. George Floyd had died, and the whole world was protesting his murder. I thought let me tell the story how I feel it’s so important in America particularly, but worldwide, for people to understand the African American experience did not start with slavery. There’s a whole history in Africa of Kingdoms and Dynasties that we don’t learn about in school. I’ve heard some people in other countries do learn a little bit about that. But I felt like let me make a real point here and go all the way back to that we literally all came from Africa.

You know we were royalty, then we were enslaved, and the whole thing went around the other way and then we were emancipated. We started creating blues and then we created jazz, etc. As black people, we were contributing something really important. Also, bringing in Malcolm X and the death of Martin Luther King Jr. That was part of the whole experience as we progressed, until we get to the point of the end of the video where I am saying: You know what we’re all from the same human family, it isn’t about black vs. white. When I show some of those pictures at the end, those are people in my own family, because my family is quite diverse. I have a brother that is married to a Japanese girl and they have kids. My other brother was married to a Mexican woman, and they have mixed kids. I was married to a white guy from Kentucky, so there is all this mixing and blending. That’s what we show at the end of the video, that we’re just all human.

AFG: Has your view of the album evolved over the past four years?

LM: I believe it’s the kind of record, because we weren’t trying to fit in any particular popular sound, that it’s timeless. The songs just have this timeless thing about them, which Pink Floyd’s music has anyway. I also feel that about the originals on here because of the approach Dave took to the production.

DDF: There were certain songs that would definitely usually take a Floyd edge, and could easily have gone down as almost an original song. It could have sounded exactly like Pink Floyd. There were Pink Floyd covers that we could have done exactly like Pink Floyd, and from my point of view, I was specifically trying not to do that. To use two songs as an example: the first is your (Lorelei) cover of On The Turning Away. When we got that through, there were drums and bass and I think that bass on Turning Away was played like a solo for most of it. I cut a lot of it out and added a few key bits and I did my own low-end bass underneath and just brought him in for little moments in between the vocals.

The rest of it was kind of like open season for me to just play whatever I wanted guitar wise. The one thing that I didn’t do was get my Strat and plug it in with the usual Gilmour sound and play it like I would in this band [The Australian Pink Floyd Show], which is a Pink Floyd tribute band. If we played Turning Away tonight, which we’re not – but if we were, it would sound like Pink Floyd. The first thing I did was use a Les Paul. I needed a different guitar sound and to take all the comforts away from me. All the things that make me play like Gilmour. That then made it more interesting! There were moments of it where I was using like Open Wah sounds like the Money For Nothing “Knopfler” sound, and I was finger picking bits rather than playing with a pick. We also changed some of the chords where there might be a G we would make it an Em or a relative chord of that, to give it a different sort of either darker or lighter feel. It’s a Pink Floyd song, but it’s not a carbon copy. I spent my life carbon copying Pink Floyd! [laughs].

I didn’t want to do that on their album, because I didn’t see the point. That’s the first example, the other song I was going to say was Cocoon, which is Durga’s song. Originally, Dave (Kerzner) was going to work on all of Durga’s songs but then it all ended up coming over to me because there was a consistency of sound we were trying to achieve at that point. I remember getting that through and there was no guitars on any of that. It was like keyboards Dave had done, and bass and her vocals. My solo at the end of that is probably one of my favorites because it goes on two or three different sections: There’s like a clean crunch section, then there’s a big Strat lead section, and then I have got this “Knopfler” sort of finger picking Les Paul thing at the end. I was deliberately not trying to make it like Gilmour, I wanted it to be different.

LM: Choosing On The Turning Away was also partially acknowledging the first time we worked with Pink Floyd. They were promoting A Momentary Lapse Of Reason and both Durga and I are in the official video for ‘OTTA’. It’s also the message behind the lyrics, they convey a profound message that resonated with us, emphasizing the importance of acknowledging and empathizing with the suffering of others, even if they are strangers in a distant part of the world. It served as a reminder that as humans, we should extend our compassion beyond our immediate circles and strive to alleviate the pain and hardships faced by those who are unknown to us but are in need of help. That is a timeless message.

DM: I just looked back on it now with a great deal of pride. I was actually listening to Goodbye Blue Sky last night, and I was thinking about how much I love what we created. We made this album with a great deal of reverence. I hope that shows.

AFG: Durga, your writing style is both charming and inspiring. When did you first realize your talent for songwriting? The lyrics for ‘Gods and Lovers,’ which explore themes of love, desire, and the sacrifices associated with love, are truly beautiful.

DM: Wow, thank you! I discovered that I could write lyrics when I was in my early teens, despite the fact that I was more interested in acting back then. Then I got into songwriting in earnest in my early 20s. I wrote Gods and Lovers with Jon Carin. It’s one of my favorite songs I’ve ever written. It’s actually an homage to Joni Mitchell musically, and we used one of her signature open guitar tunings. The original demo actually had a percussion sequence from Learning To Fly.

On tour during soundcheck they used to always have to run it, and in my head I heard this four on the floor kick drum going along with that percussion sequence. Jon still had it (shhh, lol). When I explained to Jon what I was hearing, he was shocked that I came up with it! but it worked brilliantly. Fast-forward to the recording of this song for Black Floyd – I asked Jon if he would play some keyboards on it. We sent him the track, and when I heard what he played when he sent it back. I actually started crying because it was so beautiful, and I’m proud to say that I actually played one little keyboard part on it myself.

AFG: Let’s talk about the funkiest song on the album: ‘Money Don’t Make The Man’ what was the inspiration behind this song? I identified a thematic connection with this and ‘Have A Cigar’ (which Lorelei nails beautifully on this album) about ‘success.’

LM: Basically, it’s talking about how people in power abuse their power. That’s why I’m describing this rich guy in his limousine flipping through his phone going: “Who am I gonna call now that I’m in town?’ That’s what I’m talking about. This guy calls up this girl and says “Hey baby, I’m in town, my wife’s not here.” You know, that’s typical.

DDF: You mean half the people we tour with? [laughs]

LM: [Laughs] Certain wealthy men. I was thinking about a couple of different rich men, one that I knew quite well. But another that, at the time, because of what was happening in our politics, was also quite visible, as a powerful man that could kind of screw over anybody. I felt like it was an important message to put out there.

DDF: When we got that track through originally, you had a backing track and I tried to put guitar down on it and I was getting bored by my own playing on that. Thinking that this has been going on for ages and I had arrived at that Leslie driven guitar Any Colour sound, I then wrote up Dave and asked “If I play for a bit and then I stop, can you then do some keyboards in between with Any Colour You Like sort of delays on it?” And he did and sent that back to me and I loved what he did on that. He just knew and had the sound straight away. Then, of course, it did all end up coming back to me to fiddle with anyway.

LM: That was Dave Kerzner’s band that had done basic tracks after the cruise, where we would all play together in the studio and I sang that live. Which is the way I love to work when I can, and it just worked!

DDF: I’ll tell you what was interesting about that one as well, because I had actually done a mix of it, I played the guitars, and I had done that thing where it breaks down and you get that sort of vocoder with bass on it and then there’s these distorted drums in the passages. Lorelei wanted Tom Lord-Alge to mix it, which I understand, he’s a Grammy award-winning mix engineer, so I sent all the multitracks across to him. He then sent back the mix and none of those signature bits that I had done were in there, it was just the same drum track. So, he sent me back the multitrack that had been through a lot of his outboard, then I mixed it from his processing and put all my bits back in [laughs]. That was a real weird ‘round the houses sort of track. Because of that, the drums on that don’t sound quite the same as any of the other songs, because I mixed them, and then it all got run through Tom’s analog gear, he’d done a mix, then sent it back to me and I then remixed it from his mix. It was a strange ol’ beast, that one. [laughs] But I do love it because it’s got a character to it that some of the other tracks don’t have.

AFG: The harmonies in ‘Love of a Lifetime’ are truly remarkable, the song in general has the essence of a late 80s pop/rock song. Could you explain the inspiration behind that catchy melody? It has a quality that feels radio-worthy!

DM: Thank you! Oddly enough, the same guy inspired both Gods and Lovers and Love of a Lifetime. He was someone I dated during the Division Bell tour. Ahhh, the angst of heartbreak, hahahaha!! it definitely makes for great songwriting material. Love of a Lifetime was one of those songs that popped into my head completely formed one morning. I sat up in bed out of a dead sleep and the hook was in my head. I have a theory that many songwriters who have died are still creative on the other side, so sometimes they pop their creations into our heads in our sleep. Those of us who are open to receive their gifts, anyway.

AFG: Lorelei, how did you and Durga decide vocal duties?

LM: That was something that we kind of just knew. I do Have A Cigar. She does What Do You Want From Me. We didn’t have to really discuss it, we would just say: “I want to do this one, I want to do that” and we said “okay!”

DDF: What Do You Want From Me was one of the ones that I enjoyed the most playing, because I think I did all of the guitar and keyboards on it.

LM: You did.

DDF: Again, that was just so much more filthy and bluesy rather than that Gilmour big delayed Strat sound, it was my hollowed out ES-330 and my little Blues amp mic’ed up, I loved that!

AFG: That track itself had taken on a whole new life of it’s own with Durga on vocals.

DDF: Durga did a great job singing that! I really enjoyed working on her songs. At first, I wasn’t going to be working on any of the songs that she was involved in, so I did really enjoy that. I mean Gods and Lovers – what a song that is! That became one of my favorites and I pushed for that to be first on the album because I just thought it set the tone followed by Money Dont Make The Man. It’s a great start to establish before you even hear the Floyd covers.

LM: We wanted to establish that we have our own ability not only as songwriters, but we had a style that we were trying to bring, that we felt complimented the Pink Floyd songs but was original.

AFG: Dave, what was the biggest challenge as producer?

Dave Fowler: Audio/Visual Production, Guitarist, Writer, Programmer

DDF: Some of it was people management. Which is a huge part of any kind of production, leaving aside the music. Once the decision had been made that I was finishing this off (Durga made that decision), it was then getting people to hand over the multitracks, and I been there myself, so Im not putting any blame on anyone but there’s plenty times where they go “Oh yeah don’t worry it will all be done” and then actually there’s very little done. Then I would ask whatever it is today just hand it over now, it just needs to get done.

Also, making people feel comfortable when you go back to them and say “What you done isn’t up to standard, can you do that again?” You’ve got to say that in a way that makes people want to do it. There were times I said “This wasn’t really good enough, can you do it again by this date?” And if they didn’t do it by that date I would either find someone else or I’d do it myself. There were a lot of people on this album and a lot of people with egos.

LM: Yeah.

DDF: That I would say was much more challenging than any of the musical stuff. Because from my point of view, the more people went “I’m not doing anything, you just deal with it” the more I could play with it and I’m not saying I’m the best player in the world, but it would be consistent. I know that I could finish a track, and it would be to a certain standard, and we would get it done! There were times I would have to lay down the law on things, and there were times when I had to suck it up and say: “No, I have to work with this take here that I don’t like.” Sometimes on the album, if you hear things that are covered in a delay or distorted and put in the corner, that’s just because of the source material I was dealing with.

As an example, certain vocals that came from Durga. It wasn’t her performance. The performance was fine, but there were ringing frequencies in whatever room she was in, and whatever mic she was using and it just sounded horrible. It would have been so much easier to re-record them all, but then she’s sitting at home during the pandemic, and she can’t get to a studio. She’s got her mic at home that maybe is worse than the one I’m dealing with.

Sometimes you just have to deal with that and there was a lot of that struggle during the pandemic. Where in a normal situation, you’d say: “Go to the studio, re-do these three songs, run them through a nice preamp send me the files, and it will all be good.” You couldn’t do that, there were limitations. I had to do a bit more rescuing of things than I’d like to do. The bottom line is, I was given ultimate freedom by all of them. Someone had to make the decisions and that was me.

LM: I had similar limitations as far as trying to make music videos, because we were still in lockdown. Durga was on the West Coast, I was on the East Coast. The only one I really put us in, she got someone to go to the beach with her to film for Gods and Lovers and I got someone to go to the park with me in New York where it was winter, and snowing. I thought it would be an interesting contrast. She’s at the beach, and I’m in the snow. That’s kind of cool. As for the images, I used them to try to tell the story of the lyrics, and it was because I didn’t have the camera work available to me like a normal music video where you would film people actually doing things. I had to tell the story with pictures. It’s kind of a style, but I also tried to do my best to work with the limitations, plus I’m not a professional editor, Dave (Fowler) taught me how to edit during the pandemic. So, I did the best I could.

DDF: I think it was important to put your vision on those things, and having some kind of visuals with the video is better than nothing. Even if it wasn’t perfect, it’s still better than not having it on YouTube or having it with a static song title or a single picture.

AFG: You were improvising.

DDF: We were, I don’t know how much understanding of that people will have in ten years’ time. There will be people who will go “What’s COVID?” [laughs] because they won’t remember, and they’ll judge it based off that. We had a whole thing with a couple of songs with Paul Bonney, our drummer from Aussie Floyd, who played drums on a few of the songs. I programmed drums just so that we could get on with the recording, but we wanted real drums, and we were waiting for things in the UK to open up to enough of a degree that someone could go somewhere and set their kit up in a room and put some mics round, then send me some files.

I had contacted several people, in the end Paul Bonney set his kit up in his local pub in their back function room to practice because the pub wasn’t open, and he could get in around the side door “illegally” but they would just give him access. [laughs] A friend of his came down with some mics, and then put like fourteen mics around the kit and just set him up so he can hit record, and he’d play along and give us a few takes. It’s got a nice sound in there! [laughs] its a live venue room so…it’s nice. What’s great about Black Floyd – I say great, but the challenges, like ninety percent of the challenges there, are not challenges that we’d ever have on an album now.

LM: Right.

DDF: They’re totally different challenges, it’s a total one-off. We were just doing what we could in the moment with the restrictions describing where we’re at.

LM: I agree.

AFG: You mixed some of these tracks on a live stream during the COVID lockdown, were the versions of the tracks you mixed on live streams during lockdown the ones that ended up on the finished product?

DDF: Yeah, they are, and I’m not saying whatever I mixed in that live session ended up not being tweaked again, because as you end up doing more tracks you go back to the other ones and go “Oh the snare is a bit louder there, etc.” But I just started live-streaming as a bit of fun really. Other people were sending me songs to mix that they were recording at home, and I’d go “I’ll do your mix for free if I can do it live” and then it became YouTube content. Actually, out of that YouTube content I’d take clips of me using a certain plugin or doing a certain technique, which would end up getting thousands of views on my YouTube channel. It got me a few thousand subscribers to the point now where if I do put out a few tips and tricks, it actually brings me some income now. I just started by accident during the pandemic. It was a way of connecting with people, because while I’m sitting there mixing rather than doing it on my own, it’s me on camera and I share my screen and I can get on with my work and if there are people listening, it would become like socializing virtually. It’s been enjoyable.

AFG: Since you wear many hats on this project, Dave (Guitar, Organ, Programmer, Producer. Etc.) are you self taught in all your roles?

DDF: Yeah, sort of. It all depends on what degree. Guitar wise, I muddled along till I was about thirteen without having any formal lessons other than maybe a couple at school where I’d learn like the first three or four chords, but that was it. Then I went for a ten-week course at a place called the Musicians Institute in Wapping. It’s not there anymore. That was wonderful. It was forty hours of intensive guitar training. Most of the students there were middle-aged men who were trying to get away from their wives [laughs] who, over the ten weeks, would slowly drop off, because they realized that it was an actual proper school teaching guitar. Not just come in and have a social club with your mates [laughs]. It was hardcore. For someone like me, I was in there going “Im going to be the best!” “Im going to get every note!” [laughs]. That gave me all my music theory and technique. It gave me all the building bricks I needed to be able to become a guitarist.

Dave Fowler on stage with The Australian Pink Floyd Show

Production wise, I always had a setup at home, so I had a 4-track, and then I had an 8-track ADAT setup. Then I bought a 16-track reel to reel machine when I was eighteen, and a 24 channel desk and some outboard. Then I got involved in the studio that I bought that equipment from. Which is funny because they needed to borrow it back to finish some sessions that they had on the 16-track, because they moved up to 24. So I ended up taking some of that, then they had sessions that their engineer couldn’t make so they offered them to me. Then they were working on a new control room and then they ran out of money, so I was eighteen and went and got a bank loan to give them to do that. So I bought into the studio very young. Then, basically, I became the main engineer there and worked there until I was twenty-six, recording bands and doing basically what I was doing for them [The McBroom Sisters].

I was learning my craft, and I didn’t have a clue what I was doing. But, if you spend that long doing it you’re like; “Okay, what did I get right and wrong on the last thing I recorded?” “Oh, I love the drum sound, but my toms weren’t very good.” So on the next recording I don’t really care how it turns out, I just want the toms to be good. As long I get the toms good on the next customer, then I’ll be happy! I’ll tell you in two years I got reasonably good, and I listened back to those old recordings and most of them sound good. But, I had no idea why they sounded good. I just had techniques that I would do on real physical desks and an outboard that would sound good. I’m old enough when it was tape machines and analog gear back in those days [laughs] but when it went digital, I really got into the details of it.

I started to learn more mathematically what it was doing to the point now where I’ve actually coded my own EQ’s and Compressor’s, so I really know what’s happening under the hood. Nowadays, on YouTube there’s a million and one people who know how to do every trick, every technique, but you can’t mix a song with tricks! You mix a song by making it sound good, and then you solve individual problems with tricks. So, I’m very self-taught but I am quite scientifically minded. I’ve iterated somewhere I don’t feel out of my depth now. I’ll sit with Tom Lord-Alge who’s way above me, but I won’t feel like I’m out of my depth in a conversation with him.

AFG: How was the decision made to incorporate modern technology, specifically Nick Mason drums by Sonic Reality, in the impressive recreation of ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’?

DDF: Well, I think the fact that they were there and Dave had them on the multitrack and he said, “Well, here’s Nick’s drums with him doing a whole take of The Great Gig In The Sky…” So that is him playing. It’s not like they’ve taken samples, and we’ve programmed it, that’s just Nick doing it and, as far as I know, he did it as almost like a warm-up. So that is not part of the sample package of Sonic Reality, that’s just him on the side playing.

That’s one of those where Dave had played a piano on it as a guide for them (Durga and Lorelei) to sing to. It wasn’t in time with the drums because it wasn’t done to the drums, so there were timing discrepancies and I sort of stretched the piano to fit the drums and got them to re-do their vocals on it so we could use those drums and other bits. So we got Jason Sawford who is the keyboard player with Aussie Floyd, one of the founding Aussie’s, to do it, and then it fit the timing, and it sounded better. It’s not that Dave couldn’t do it, he’s more than capable of playing it, he just never got back. That was one of those where I needed to be harsh and just say “If you don’t get back in touch you’re off the track.” [laughs] No, but I love Dave to bits, I have complete respect. He started it, and the bits he did were great and we have got on since, and he’s a great player. He was making his own album and, of course, everyone was dealing with all their own lockdown stresses as well. No slight on him at all.

AFG: Lorelei, in ‘Forgotten How To Smile’ musically a lovely rock ballad with that hook of a chorus “I don’t know what happened to us baby, I can’t put your face back in my eyes. The days alone, the nights are never ending, forgotten how to smile.” written with Lemmy Kilmister, a name not usually associated with Pink Floyd. It’s been said you met Lemmy after a Pink Floyd show in Germany in 1989, can you speak on how you two collaborated on writing these really heart-rending lyrics?

LM: He and I met in the bar after the band had come back from playing. As I recall, it was Hamburg, Germany and we just kind of hit it off. I remember meeting with him again, and I told him, “I got this lyric I can’t finish. Would you help me?” He said yeah, and he gave me a handful of lines in it, because most of it I had written myself. But those lines really worked. He was just such a nice, easy-going, really kind person, and he liked my singing and he just wanted to be helpful. Actually, he told me I reminded him of a girlfriend he had years ago who had died from a heroin overdose. So, it was like a familiarity in a kind of way. But in a nice comparison, obviously I’m NOT a drug addict, I’m not a heroin addict [laughs]. But the fact that he felt this kind of kinship to me was nice.

DDF: Only in the music business can “you remind me of a friend who is a heroin addict” be a compliment! [laughs]

LM: Also, my original demo was completely different. The feel of it, the drum pattern. It was more.. I can’t say jazzy, but kind of like, almost neo-soul-ish. You know I learned over the years that any song can be done in any style. So it didn’t matter. So when I brought it to Dave, I was like: “We need to make this work for what this project is.” So we made it a rock ballad.

DDF: That was particularly interesting because that was the first one I did all of. That was completely independent of the other Dave’s recording with her. I was kind of playing this Hendrix style guitar in the choruses, but go and listen to a song called Weak As I Am by Skunk Anansie. That’s a massive influence from my point of view on the way I wanted to take it. But then the verses where Lorelei wanted that kind of fretless bass stuff, and it’s a lot smoother, was more like the original demo. But the choruses, are me trying to add the Skunk Anansie, sort of the rock thing on top of that. Which, I don’t know how big they were in America, but they were huge in England and that guitarist is amazing!

AFG: What was the experience like during the recording of ‘Cocoon’, a track that has a sound reminiscent of Pink Floyd and could seamlessly fit in with The Division Bell? Did it become evident during the recording process that this was intended to be an epic Floyd send-off for the album, or was that the initial goal from the beginning?

DM: Dave Kerzner has a great love of Pink Floyd. And we definitely wanted to create an homage to them with this song. I wrote the lyrics originally as a poem inspired by a tough period in my marriage. We wrote the music together somewhat organically, and it just turned out perfectly. I’m very proud of that song and the fact that you would say it would fit on The Division Bell is a huge compliment, especially coming from you. Thank you.

LM: It wasn’t anything we really talked about. For me, personally, I didn’t like the song. Durga loved it, Dave (Kerzner) and he loved it [points to Dave Fowler], so I was like: “Well okay, my opinion doesn’t matter. You guys really love it, then make it great.”

DDF: I got that one sort of sixty percent finished, so Dave had done all the keyboards on it. The drums were down on it and Durga had done some vocals on it. Then you [Lorelei] added in some extra vocals in afterwards. But it was brethed of any kind of guitar. So I added, as I’ve said, one of my favorite guitar solos on the whole album, I loved it the moment I heard it. It’s one of those things that you can take a sound and make four sounds out of it -pad it ‘round and create a real three-dimensional spectrum with that mix. To me, it just stood out. I absolutely love it. It just created a mood that was perfect. Then there was the short track before that’s sort of like sound effects that go into Cocoon.

AFG: Intermission.

DDF: Yeah, the Intermission.

DDF: Yeah, that’s a reference to Blur’s Modern Life Is Rubbish. Back in the days when albums came on two sides, on the tape or the vinyl when the first side finished, the song faded out and it went into a piece of music that was called Intermission and at the end they would have the walkout music at the end of the second half. It was something they did on there. So, that’s just a reference to my love of Blur. Again, musically, you don’t want it to be two-dimensional, you want to be taken on a journey. You want to be able to shut your eyes and visualize it. It’s got to surround you.

There’s a lot of stuff going on in Cocoon. There are the violins that Lili Hadyn did over the top, which personally I think sounded awful. But she was a friend of Durga’s, and she really wanted them in, so I had to be really careful about putting them in places where they worked and pulling them out where they crowded other bits because you couldn’t just have them over where the singing was because it would have just ruined the mix. It was like two tracks of violin that were clashing with each other. It wasn’t like it was a worked out part, it was someone improvising, and you can’t put both of them on all the time. It just sounded bad. Don’t get me wrong, she’s a great player, but I had to be really careful. It was a case of getting them in enough to keep Durga happy and getting them out enough to keep me happy [laughs]. To me, that was a wonderful song, that and Gods and Lovers were Durga’s crowning moments.

LM: She’s always been a really good songwriter, in my opinion. I love her lyrics. I’ve always loved her lyrics. I’m not anywhere near as good at lyrics as she is. So, I was really happy the way people responded because, in general, Pink Floyd fans really love Cocoon.

Guy Pratt with Lorelei and Durga

DDF: The one I probably had to do the most work on was Durga’s called A Girl Like That because none of that matched at all. That was the one where I initially programmed the drums, then Bonney had to re-do them. Then the piano wasn’t in time with the bass, they were both pushing and pulling in different places. So, I re-played all the piano on that. The only thing I think that stayed from the original was the vocals and the bass, because we thought the bass was Guy Pratt. We were told it was Guy on bass, because he wrote the song with Durga. Then, about a day before the release, Fernando Perdomo said “No, that’s me playing bass!” [laughs]

The problem with the demo was it had been done with no click track. It was completely unusable. So I replayed everything else and I made sure we got all the grooves exactly right, and then I sent it to Bonney to match the drums, and we based the whole thing off this bass line because we couldn’t not use it. It’s Guy Pratt! Then Fernando said no that’s me, [laughs] Guy’s was different. So then Dave Kerzner found Guy’s bass file, sent it across, and then it didn’t match up. We asked Guy and he replied “Well, what the guy’s done is fine.” So, Guy didn’t end up playing bass on it, which was a shame. Because I’d been misinformed that it was Guy.

LM: I thought it was Guy too. However, Fernando really played in his style, which is why we were fooled. We added that song on the album because I requested it. It’s one of hers that she’s written that I just thought that was a really beautifully told story of what Women go through when they’re mis-judged because of the way they dress, if their too sexy or too forward, etc. There’s this assumption that she’s a “slut”. Well, maybe she’s not, maybe actually she’s a human being that has sexual interest, but that doesn’t mean she’s to be disrespected.

DDF: That was probably the only time me and Durga disagreed was on this track. I had made a mix that was more to my taste and aggressive with the guitars. I really enjoyed the mix of that, but she didn’t like it. She wanted it not like that. I expected to disagree with her on almost everything, but actually there was very little difficulty at all. Which was nice.

DM: On Cocoon, it was also my idea to ask the incomparable Lili Haydn to play violin. She’s a dear friend of mine so she was happy to do it. I really like how ultimately it played off of the unbelievable solo that Dave Fowler played.

As a matter of fact, we owe Dave Fowler a huge debt of gratitude. without his expertise and generous offer to step in and deliver an amazing mix, we never would have had the results that we wound up with. I will always be forever grateful. Not to mention the fact that he plays his ass off on everything he played. That guy is a musical genius.

AFG: Durga, can you explain how you came to write the lovely enchanting ballad ‘A Girl Like That’ with Guy Pratt?

DM: We wrote it during my Blue Pearl phase when I was living in London. I had just done a big interview, and I was very excited to read what the interviewer said. We covered many deep topics. Imagine my disappointment when the very first thing that he said was “It’s her legs. They go from her neck all the way to the ground”, or some other such drivel. I wrote this song to explain that I was not just some sex pot. That I have a mind as well. Guy had a studio in his house, so we wrote a couple of songs together. That was the best one.

The McBroom Sisters and Rachel Fury in Pink Floyd: Live in Venice 1989

AFG: As a listener, I drew conclusions that this album in many ways captures the essence of Pink Floyd. The band is known for honoring their musical roots and Black culture in Rock and Roll and honoring their fallen leader and friend Syd Barrett throughout their entire career, much like this album honors the musical journey with Pink Floyd and the roots of The McBroom Sisters. How crucial is it as an artist to maintain that moral integrity and authenticity in their work?

DM: Well, obviously that’s the crux of the matter, isn’t it? To me, as an artist all you have is your word, your expression. If you lie, what’s the point? I always strive in my lyrics to be completely transparent and honest. And I’ve had people tell me that I put into words things that they didn’t know how to say. That’s a lot of why I do what I do.

LM: Well, given the fact I had a record deal on Capitol years ago, and they signed me because they liked what I was about. But, they wanted me to change who I was to what they thought they could get on the radio. Going through that experience, I was like this is not who I am as an artist. Like I said before, I grew up on Folk music, I didn’t grow up singing in church, not to say that I can’t be soulful, because doing blues definitely puts me in touch with that part of me. But I was singing Joni Mitchell songs and stuff like that. This [Black Floyd] gave me a chance to not worry about whether is this radio worthy? or is this going to be a hit? Just do good art and let it find its audience, instead of picking the audience and trying to fit in there.

AFG: Were there any plans to tour this album globally post COVID? Perhaps during the off season while also performing with Aussie Floyd?

LM: Well, we initially had the gig on Cruise To The Edge, which got pushed back a couple of years and that was kind of the start. But then, given that we were trying desperately to get back to work so we could make a living, it was really difficult to even think about trying to do any kind of tour to support the album. So we didn’t even try. Again, so much of it was because of the pandemic. It’s like the bottom was pulled out of the business. Loads of gigs that Durga had got booked on got cancelled. I was just lucky, because I’m in the Aussie Floyd, so that once we could go back to work, we did. The gigs were there because we had already built the foundation, not me- but the band. Thirty some odd years of touring, we had a foundation. So I was able to work. So I had to put it aside…who knows now.

I personally feel if we were to get the support behind it and put the record out even now, it would still work. Because we weren’t trying to fit into any particular genre that’s selling now or that’s “it” now, that it doesn’t matter and that it could be done. I have my mind on other things at the moment. I have a show on YouTube called “Who Influenced You?” where I have been interviewing different people, mostly music people, because that’s where my closest, lowest hanging fruit is, is music people. So I have been focusing on that.

AFG: Will there be a McBroom Sisters follow-up record?

LM: I don’t know, we really haven’t talked about it. I definitely would like to record some more, because the album I did on Capitol didn’t come out. I also made an album with my son’s father, who is a founding member of the Uptown Horns. We met on The Stones tour because he was in the horns section. We did a project with our house band. It was a really cool blues album that never really got released properly. So, I feel like I missed the opportunity to be the solo artist that I wanted to be all along. It’s just the tours I got on were very high profile [The Rolling Stones, Rod Stewart, Pink Floyd] they were lovely, and I like that they all gave me a chance as far as a solo moment. But, it’s still in me to want to be that lead singer, because I am.

DM: Obviously, we would love to do another one. It would be really difficult to re-create what we did here. If there’s anyway we can figure out how to get it done for a second time we will.

Black Floyd by The McBroom Sisters is available to purchase by clicking this link.

Follow The McBroom Sisters and David Domminney Fowler on social media to keep up with their current projects.

Durga McBroom: Facebook | Instagram | YouTube

Lorelei McBroom: Facebook | Instagram | YouTube

David Domminey Fowler: Facebook | Instagram | YouTube

Dave Fowler, AFG Editor Tony Rapata, and Lorelei McBroom backstage in Chicago, June 2024.

Special thanks to The Australian Pink Floyd Show, Steve Mac, Chris Gadd “Gaddie”, Lorelei McBroom, Durga McBroom, David Domminney Fowler and Lee Harris.